Three-time Emmy-nominated Cinematographer Bob Richman Discusses his Career

Three-time Emmy-nominated Cinematographer Bob Richman joined us to discuss his work on "The September Issue," "Metallica: Some Kind of Monster,"and the award-winning Documentary "Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills" and his decades shooting documentary films.

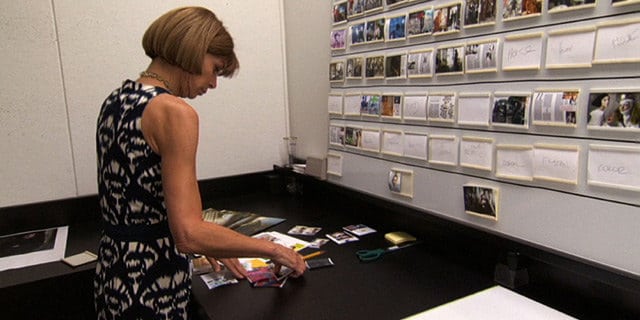

Cinematographer Bob Richman began his film career working with vérité pioneers Albert and David Maysles, quickly transitioning from production assistant to camera assistant then operator. Finally he made the leap to director of photography on the Maysles’ "Umbrellas," which chronicled artist Christo’s installation of three thousand umbrellas north of Los Angeles and Tokyo. Today, Richman is an Emmy-nominated and Sundance award-winning cinematographer on almost a hundred documentaries including: Davis Guggenheim’s "An Inconvenient Truth" and "Waiting for Superman," Nathaniel Kahn’s "My Architect," Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky’s HBO films "Paradise Lost" 1, 2 & 3 and "Metallica: Some Kinda Monster," RJ Cutler’s "The September Issue," "Oprah’s Master Class" and Sundance Channel’s "Iconoclasts."

---

Gordon Burkell (GB) - At Filmmaker U, we create courses for film professionals to deepen and diversify their existing skill set. Every Friday we invite a film professional to chat with us. Today I am joined by Bob Richman, the cinematographer for some incredible documentaries such as "Metallica: Some Kind of Monster," "The September Issue," "An Inconvenient Truth," and "Paradise Lost."

Bob, when you are preparing for a shoot with a new director, how do you get inside the director’s head so that you understand what they're going for with the film?

Bob Richman (BR) - At this point, directors usually understand what I do and they hire me because of that. In a vérité situation, I really consider myself a co-director. It's like basketball, the coach can tell the player when to shoot and where to go, but he has to trust the player knows what he is doing. The director has to trust me. Having said that, every director is different. I've been working with Joe Berlinger for years and we're usually on the same page. I worked with Nathaniel Kahn, the director of "My Architect," and the way we worked is that we would talk before shooting, and then we talk after shooting, very rarely did we talk during the filming. We'll talk about what we think we're going to get but there's always that danger of taking too much about what you think you are going to get because things never quite turn out the way you expect. Oftentimes, you can make the mistake of missing something important because you've thought too much ahead of time about what you think a scene is going to give you. Something happens and at the time it doesn't seem like it's relevant and so you don't shoot it. Then later on, you say that was important! Every time I am in Sundance, they send these questions around for all the DPs and it's the same question. They always ask me do I bake-in the look. If you're doing a feature film and narrative film, you need to think about how it should look, but if you're doing a vérité film, you don't even know how the film is going to turn out! So you just want to make it look good. You don't want to bake in any look that isn't appropriate until you know what the finished film is. So it's always an act of discovery. At least that's the way I look at documentaries. That's what makes them fun for me. That it is a journey you go on with the director.

GB - You and I have been chatting about teaching. One of the scenes I show in my class is from "Harlan County, USA" and it's the union scene just before the gunshot goes off. The reason I show that is because of the way the cinematographer was able to capture all the people in the union meeting. It seemed as if the cinematographer knew who each individual was and how they would play out in the edit. How much research do you do beforehand so you know each of the people in a large situation like that? How much is it based on what's happening live?

BR - Usually, I don't! Hopefully the director has done that research. That's the wonderful thing that a director can do for a cinema vérité cinematographer is to build trust with the characters. Start by building trust, and getting to know who the characters are. You never know what character will emerge. You might assume that one person will be the lead character, but then some other character emerges and dominates the film. That's where a director has to really have discipline to say, "Okay, the film's going to be about this person. Even though I got great footage of these other people, this is who the film is about." I have to build my own trust with the director and my sound person, because trust is really the glue that holds those type of films to together and trust takes time. The first few times I film someone it is oftentimes awkward, and not great. Then as time goes on, if you've done your job right, and you have built trust, and love, they open up more and more. You get to know them, and they get to know you. Oftentimes right at the end, the last filming you do, it's like peeling away an onion. You say, oh, now I'm getting it. What happens to me often is, I get to that point, and then the film's over, and then I have to start another film and I can't understand why I’m not getting this great footage. I forget the process of building trust, to get to that point where somebody opens up to you.

In the doc, "The September Issue," Grace becomes the star of the film but at the beginning, Grace wanted nothing to do with the film. The director R.J. Cutler didn't know who she was. We filmed for months, then the director read a book about Grace’s life and he said, 'Oh, we've got to film this woman and you have to build a relationship with her.' After months we built a relationship with her and she becomes the star of the film. I was very lucky to get my start with the Maisel brothers. There has always been this concept in documentary vérité, that the crew and the filmmakers are like a fly on the wall, where nobody notices you. I think if you develop enough trust, your characters become almost collaborators. That's not to say they influence the nature of the film, but you're telling their story. At some point, they realize, that actually, they're telling their story. They're using you as a vehicle to tell everybody their story. Then instead of them feeling like an insect under a microscope, which is what they feel like in the beginning, at some point they realize, no, I'm telling my story through you. That's when you get the great stuff. That's when they trust you, and they're opening up, and you're getting this wonderful stuff. And that's what happened with Grace on on the highest level. I was in the film also. She turned the tables on us in the end.

GB - Do you have tricks or techniques to build that trust with your subjects?

BR - I wouldn't call it tricks because you don't build trust by tricks. I like to treat the subjects as if I didn't have the camera. You have to earn the right to film. Sometimes you get into a situation where you're filming on the first day, they hardly know you and all of a sudden, it's an emotional scene. The person starts crying and I've found that the smartest thing to do is not to film that. You haven't earned the right to film something that intimate. Of course, as a filmmaker, especially a director, will say film that! We want that! Sometimes it might be right, sometimes it might be wrong, but what I found is if you show that respect, you earn something that you will get back down the line. That takes a lot of courage and faith in that system, but I believe in it.

GB - What have you been doing during the pandemic?

BR - I am organizing my old negatives, and actually looking through footage of a film I've been shooting for the past eight years. Biking, a lot of biking. I've been biking and working out, hoping for one day to be back with a camera on my shoulder!

GB - One of the things that you mentioned earlier is the importance of your sound person on set. I've talked to other DP's who work in documentaries and they've said the same thing. What is it about that relationship? I almost feel that there's some kind of communication occurring that allows you to work better?

BR - Camera and sound is almost like a duet. We are working together. I so depend on a good sound-person. There's a saying, “what makes a really good documentary cameraperson, is a cameraperson who listens”. I always say that what makes a really good sound person is one who watches and sees. A sound person is another set of eyes for me. They have to know how you move. I've seen sound people who don't know. I will often be filming a person here and the sound person is standing over there, and I am going to have to pan through the sound person which is not good. They have to know how to move with you and they have to be listening. Sometimes they're hearing something or seeing something that you don't see. Everybody on a vérité film has to think like a filmmaker, even the PA. It's a small team. It's a collaborative team -- that's what's fun!

GB - One of the things that's always blown me away with cinema vérité, is that it is almost like you have a sixth sense of what's happening in the room - just getting to the moment before it happens. How do you develop that sense?

BR - I think some of it is the personality of the people who gravitate to this kind of work. You have to like observing people, but you also have to open yourself up to what's going on. Oftentimes I'll be on somebody who's not talking and I'm getting a cutaway. As I am getting that cutaway, I'm also listening. I'm constantly listening to what the person who's talking is saying so that I can feel the rhythm of the person talking. I might feel that they're coming close to an ending or saying something emotional, and then I'll move on to that person. I'll catch the end of their statement, then the editor has the option of just using that as a cutaway, of somebody listening, or they can use that whole movement and it'll seem like I had anticipated it. I was once asked, 'What's the difference between reacting and anticipating.' To me, anticipation is a higher form of reaction. When you're anticipating, it's because you have a sense of something, you're reacting to the scene and you have a sense of what's going on. That's just being in tune with what's going on in front of you. It's you reacting to something you're feeling inside. It's a much higher, more refined sense of reacting, you're still reacting, but you're reacting to something you're feeling is going to happen. I think we're all sort of genetically designed to do that. That's how we interact with each other. When people get a camera on their shoulder, they may lock up and let go of those feelings. All of a sudden you have a camera on your shoulder and you're worried about composing. You're worried about focus, you let go of those other things that make you aware of what's happening around you.

GB - What would you say was one of the tougher scenes in your career to shoot? Why do you think that was?

BR - Well, I don’t think there was just one but many scenes that were tough to shoot. One of the toughest scenes to shoot is a classroom scene. Especially when the teacher is lecturing and there are 30 students, and you don't know who's going to talk and the students are giving just one word answers. Those are tough scenes. The other thing that is tough is when you're waiting for one thing to happen. Somebody is going to show up, come out of a car and you're waiting for this one moment to happen and you have to be ready for it. It's too much anticipation for me. I'd rather be in the mode of shooting, and then something happens and I capture it.

GB -The most stressful thing to me was waiting for that film to come back next day, as a documentary person. Can't really re-go and shoot!

BR - It was always a little miracle actually. That was the reality back then. The fact that you only had 10 and a half minutes before you had to change reels and the fact that you only had one camera, people forget. They can't imagine shooting a documentary with only one camera! When it was film, you spent most of your time watching and listening and only shooting when you know it was important to shoot. Now you just shoot, non-stop.The trick to that, I had to learn, is to still get coverage. It used to be when you shot film you knew when you got the scene, and then you got your coverage. When you're shooting continuously, you forget, "Oh, I have to get cutaways."

GB - I feel that a lot of the editors have found that frustrating because all of a sudden, they're working on 1000s of hours of footage.

BR - It's insane in some ways, but it's hard not to shoot. When I did "My Architect" about Louis Kahn, he had a saying that 'every material knew what it wanted to be.' I kind of feel that film wants to be shot sparingly and digital wants to be shot continuously. Even though I came out of the film world, if you put a digital camera in my hands, I will shoot till I drop!

GB - Well, I have I have one last question that I like to ask everyone I interview. We've been in a pandemic, so what would you recommend people check out while they're stuck inside?

BR - You're asking the wrong person? I never turn on a TV. I like to read. I love to read!

GB - So tell me a book that I should check out.

BR - I just read Walter Isaacson's biography of Leonardo Da Vinci, which was amazing and very related. He talks about his painting and how he studied light, and how he tried to make his paintings look realistic with depth of field. He understood that focus lessens as things get farther away. He was a real observer of reality and brought all that to his paintings.

GB - Thank you so much for letting me interview you!

BR - It was a pleasure. Thank you.