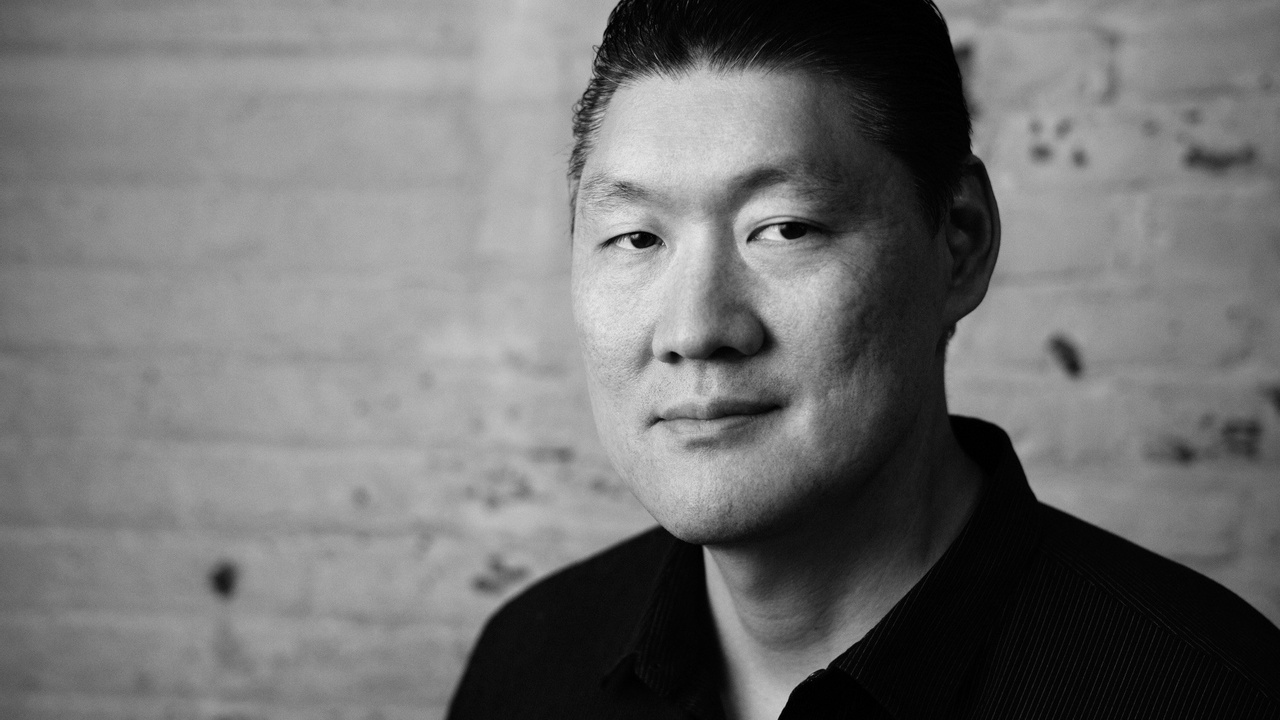

Inside the World of Color with Acclaimed Colorist Stephen Nakamura

Colorist Stephen Nakamura spoke with Filmmaker U to talk about his prolific career. His feature film credits include Da Five Bloods, Sicario: Day of the Soldado, It: Chapter Two, Crazy Rich Asians, The Martian, Alien: Covenant and many more blockbuster epics and award winners.

Among the most accomplished feature film colorists in Hollywood, Stephen Nakamura has worked alongside directors such as David Fincher, Ridley Scott, Kathryn Bigelow, Spike Lee, David O. Russell, and Steven Spielberg, as well as cinematographers Dariusz Wolski, ASC, Claudio Miranda, ASC, Robert Richardson, ASC, and Janusz Kaminski.

Prior to joining Company 3, Nakamura was with Technicolor Digital Services, where he got his start in feature film finishing. Previously he was a colorist with the Post Group, working on commercial, music video, television and feature film projects. He began his career at California Video Center.

Gordon Burkell (GB) - Hi everyone, I'm Gordon Burkell with Filmmaker U. At Filmmaker U we create courses for film professionals to deepen and diversify their existing skill set. Every week we go live Friday at 2pm with a film professional to chat and give you a chance to join us and ask questions. Today I'm being joined by Stephen Nakamura, the colorist for Fight Club, Kill Bill I & II, It, and more recently to Da Five Bloods, among many others. Stephen, thanks for coming on the show.

Stephen Nakamura (SN) - Sure. Glad to be here. Thank you.

GB - I've listed off a lot of films here. But one of the things I've noticed is there in a couple situations, you've actually got directors that you have long time worked with including David Fincher and Ridley Scott. I don't hear that as much with colorists and I'm wondering how did these relationships evolve? How do you go about developing relationships like that, so that they last long term?

SN - Well, I think the real key for colorist is you really need to get in tune with the director sensibility. Most people go back to the same person that cuts their hair, right, because you don't have to tell this person how to cut your hair, it's a lot because they know what I like. It's really your ability.

When we're on this side of the production and post production, to really say. Hey, I'm going to try to get in tune with this director, and what their sensibilities are. And once you can connect that way, then there's a real shorthand for communication. Which makes it really simple for them, you know, because they're, typically during the finishing process, they're doing the mix. They're doing audio. They're finalizing visual effects. So they're working on in a whole bunch of different areas. I think the last thing they really want is to just be doing more minutia stuff with color. So if they have a shorthand with their colorists, and they kind of trust it, their colorists can paint pictures for them that the way that they find pleasing for a particular movie that they're doing, then they'll come back. Especially if you make their lives easy for them also.

GB - Now, there's so many people involved in the look of the film, you know, there's the cinematographer, but there's also set decorators, there's also costume departments, how do you work with all the various people but particularly the cinematographer and director to get a particular look for film.

SN - You know, usually you have a conversation with the director and cinematographer beforehand. And so that you get an idea of what they think the movie should be, and what it should look like. A lot of times, you also get to see the dailies cut together from the avid. So if they were, if there was a colorist on set that was setting looks, you can already get a glimpse of the kind of feel that they want for their movie. So that makes it a lot easier, you know, just having sort of like the Avid output of the show, if the cinematographer had time dailies, whether it's with a colorist or DIT, it gives you a really good base for where you can start. And then it's basically having some conversations. You know, some directors have you know, certain preference and style for them, they look at color certain way. So once you understand how they operate, and the kind of looks that they liked, and it's very easy for you to you know, implement those looks on a different different kind of show or movie that they're doing. Even if you're doing a lot a lot of Horror, then they do a Drama. If you know their sensibilities, it's it's easy shorthand that way.

GB - I mentioned you you've been working with people like Fincher and really for a while. One of the things I noticed is you started back before we had things like Resolve and what have you. So from the old sort of telecine days, what have you learned from working in that format? Or that I guess approach to color that you use still to this day?

SN - You know, in the back when we're doing telecine, obviously, it was a film tape transfer. So if you're doing features, it's was film to film. So they will go to the lab and have a lab timer time their film, they would have printer points. You know they would have a point A red appointed green that can make a little bit bright, a little bit darker. They didn't really have the control that we have digitally when we're doing some video. So all the commercials and music videos, TV shows and stuff like that, that we would all be coloring, we have power windows, we can do color isolation, you know, we can do all those things that we're not available in the feature film realm. Then when the DI came in the early 2000s, the technology had gotten to a point where the color correctors could take on these large files that were 2K and 4k files. You could color correct it for theatrical. This was a big game changer for a lot of directors like David Fincher, for example, you know, that was the first really big DI that Technicolor had when they started in 2002. So I was working with David, and he said I want to do Panic Room, in this DI thing. And, you know, it was a, it was a pretty big move, even though it didn't seem like it was a big move is a really huge move at the time, because basically, the technology was in its infancy. So at that point, no one was really quite sure. If this thing could really work, as well as the idea was that it could work, right, because there's so many pieces of the puzzle, in order to get DI finally, you know, have a graded file that you could print on film. There's so many factors involved to get that to look right. And at the time, we're just kind of inventing the wheel. So it was a really huge move, because I'd basically giving up all my telecine clients and commercials and video and stuff like that, to move into the feature realm. And it was pretty, it was a pretty arduous process that you know, we lost a lot of our lives, I think, the hours and the, you know, the pain back in the day as equipment wasn't working. And you know, I mean, you're just trying new technology at the time. So you know, it all worked out. And so now, you know, like, doing a DI is no different than doing a commercial or music video or anything else, that it's very similar?

GB - Well, it's interesting that you would say that, because this industry is very demanding. So for example, like, you're talking about learning, the DI process, how do you keep up on all this advancement? Because it's constantly advancing? And how do you make sure that you're going down the right path? Because there might be competing versions of the DI, there might be competing software? You know, what's your approach for that?

SN - Well, I mean, the good part about being at Company 3, and being a large coloring facility like this is that we have clients in all forms of media for commercials, videos, TV, features, anything you can imagine. We have clients that need color done So as a result, the technology gets pushed from our clients, because the clients will say, hey, I want to do this, I want to do 4k, I want to do any HDR streaming, I need this, I need that, you know, and it forces us to step up our game and figure it out for them. The difference between us at Company 3, from me working from my house is literally just the technology that's involved. In order to get things done properly, on a large scale, for example, you do a huge hundred million dollar plus movie. There's so many parts that people are not aware of that needs to come together in order to get that movie to fall into place so that we can meet the deadline of that movie getting released on time and everything looking right. From multiple, you know, dozen vendors sending us stuff. Things coming in on the last minute. We have had to have an army of people just to get things done. Just from the technology and our clients having needs that we need to push ourselves to the limits of our capabilities and past. That keeps us on our toes.

GB - When you're working with directors like Ridley Scott or David Fincher, how much freedom do you have as a colorist?

SN - I have a tremendous amount of freedom. Because when you build a relationship with a director, again, I think most of the colorist will tell you the same thing. If they have a relationship with a director, they really trust you. As a result, they don't need to be there when you're doing it. Even when they come in and supervise, they're not changing that much. I think if you ask most colorists, they'll tell you the same thing. You know, so when I have a shorthand with directors that I work with all the time, though, my goal is so that the last thing they need to worry about in the finishing process of the call. I want them to just be like, I need to go work on these other things. If I got to get into the weeds with somebody on a particular aspect of my film, I can get into the weeds. But I don't want to worry about the color. Because I know that that's going to be taken care of. I mean, that's the kind of relationship you want to have. Let's say you're building a house, and you have to supervise every single person. You don't want to get into the weeds with your painter and the person that's doing your flooring, and the person's doing your roofing. It would just drive you crazy. So if I can just alleviate that aspect of their lives, so that they can just come in and go I think looks great. But let's just change this and that, you know, hopefully, it won't take that long and it's just a lot better for everyone.

GB - Yeah, it's like becoming their left arm so that they don't have to think about it.

SN - Absolutely.

GB - How do you decide between ACES, Baselight, T-Log, E-Gamut, or Resolve Color Management for your projects?

SN - It's very client dependent. Some studios have different requirements, when we're doing you know, we're talking the feature world. Some students have different requirements, we basically take a look at each project, right, so each project is done on an individual basis. You know, sometimes, I would say for the book for the bulk of movies, we can kind of push them into a certain pipeline, some other movies, you basically have to break the mold, because of certain needs that they may have. So as a result, with the conversation we'll have with the clients in the studio, if they say they want to do ACES, we'll say, okay, we can do aces. Well, what camera? Are you shooting for ACES? What kind of look Do you want in aces? And then we can kind of ship the project around ACES, you know, having ACES involved. Other times, it's like, do you really need to deal with ACES? Maybe you don't. Do you really need this? You know, and so part of part of what we do is we can handhold the clients throughout the whole process, from the beginning to the end. The biggest problems that we've had, as a finishing coloring facility is when we don't have that conversation early on with her with the clients, right? So if they start using a lookup table on set, that is not appropriate to the finishing end, a myriad of problems that will open up by the time you're at the finishing end is something that is very crazy.

GB - Pandora's box.

SN - Yeah, I mean there's so many things that most people don't even think about it, but it's really important. It's really important to know, the technology, and to also talk to the clients about, like, what are your needs, and let us help you get your project to the finish line in the easiest way possible, in the shortest distance possible. Let's just go in a straight line instead of zigzagging back and forth by doing things unnecessarily.

GB - Can you share some advice for young colorists? What would you tell young colorists just getting started?

SN - Young colorists, I would say, just make sure that you keep coloring as many things as you can, right? Because I always tell people, it's kind of like painting. If you if you take a painting class, when you learn how to paint a bowl of fruit, and you think you did a great job, and you keep painting for 10 years, and then you paint that same bowl of fruit, you're going to paint it completely differently. And you're going to look back at what you did 10 years earlier and say, oh, man, I didn't I kind of know what I was doing back then. Well its the same thing, right? The repetition and just coloring more and more and more footage. Keeping an open mind, right? So having your mind be open constantly, even if your coloring. So even for for me, I've been coloring a really long time, but it's like I'll look at a certain movie and say, I think it should have this look, because I've had that look a whole bunch of times. But it's really keeping my mind open and not being attached to anything. Right? Because maybe we can try something else. Maybe we can try this. And maybe it doesn't work. But maybe it does work, right? There's so many different tools that are in Resolve, and these color correctors and you can try different things to create different looks. So it's really kind of being agnostic about things, right. Just keep your mind open. Every time you think you kind of know it all, you just think yourself, you really don't know anything. If you just say you don't know anything, and then you look at other people's work, or you look at you know, anything, photographs and other people's work on TV or features. You can always get great ideas, and you can try to replicate it. It'll just give you more of a toolset to work with, when you have a client that wants to have a certain kind of look, you can say, hey, you can come on up your bag of tricks in your mind to come up with something.

GB - When I was researching for this talk, there was an article about you and Jill Bogdanowicz at Company 3, working together in regards to mentorship within the company and artists recruitment. How do you see? How do you approach mentorship with young colorists in your company?

SN - Most of our colorists here, started off as assistance with us before. So they kind of already know they have a good background about how we set up projects within the facility. And as a result, they have to learn Resolve because they're setting our projects up to send your projectors up for us. So it's kind of like getting that base down. And then from there, they start coloring and then a mentorship really is not just on color. But it's really about how to talk to people, you know how to handle a room. It's part of the job that maybe a lot of people don't talk about, but it's super, super, super critical, which is you have to realize that we're the last part of the chain, right? So it started off in production and then we are in post production, but not only are we in post production, we are the last people that are going to handle those images. We're like the very last people that are going to handle images before they make the DCP. So at that point, you have potentially a lot of people that are very nervous, right? Yeah, people been working on this for years, you get the director that's nervous, you get the DP that's nervous, you've got visual effects, it's nervous that all of his effects are going to look right, right? You've got the producers that are nervous, you've got the studio, that's nervous, you got everybody, and sometimes people will have different ideas about what the movie should look like. And so, part of your job as a colorist, really is to just kind of make the movie look as best as it can, and have everybody kind of not panic, and keep everybody calm. Do all those kinds of things which are, which is like a really big skill to have in our business. Part of our mentorship is not just with color, but it's really about sort of like how you handle people and how you talk to people, right? It's very important part of our job.

GB - With COVID and grading remotely with clients, how do you ensure that what they're watching as accurate, or as an accurate representation of what you're doing?

SN - Well, what we have is, we have two ways that we allow our clients to see things on their iPad. So basically, our clients have iPads and we have them calibrated the way we we need it so that the color is accurate from what we're doing. For example, if we're doing commercial music, video TV, things that are graded on a monitor, like let's say, an X300 that we grade on, we can have a setting on someone's iPad, and we can stream it to them. So that they're seeing the same thing. And it's also streaming to an iPad in my room, so I can see exactly what they're seeing. If I'm seeing exactly what they're seeing, and they're seeing our picture, then we have a good communication that the grading that work really well.

GB - It's funny that you say that because I talked to James nice for The Haunting of Bly Manor. And he had just finished doing that for Bly Manor with the iPad. He said he's never been more nervous because he didn't know would the iPad work and it was coming out the next day. So he was very stressed. So I'm sure he's very happy with the results then.

SN - That's the really interesting thing about COVID is it's kind of sped up these type of things that were going to happen anyway. This sort of was because so many of our clients are in other countries, they're in other states, by the time we're finishing, you know, it just was, it was gonna get to this point anywhere where it's like, we got to be able to let them see on some device in their home somewhere. When they're really busy that they can take a look at the color. I did the short project with Nancy Meyers recently and she was literally on her iPad in her car signing up.

GB - I hope she wasn't driving!

SN - She lost her internet at her house so she drove to her daughter's house and was in her daughter's garage. She has an iPad in her daughter's garage and we're signing off on this movie, right? It's a short movie that she did. I mean, it's just it's like, fantastic.

GB - Do you work with Color Scientists a lot, or work on LUTS yourself?

SN - Well, sure. We work with color, we have a color science team, they are completely integral to our whole workflow. We could not survive without them.

GB - How does that relationship work?

SN - Oh, basically, let's just I'll give you a like a really quick answer for that. And then it'll get more complicated, but let's just say how many different professional cameras are out there. Right? So let's just say you got you got RED, you have Alexa, you have a Sony VENICE, you have, you know, let's say five, six different cameras. You decide you want to shoot with a particular camera, right? So a client comes to you and says, I shot Sony VENICE, or next client is out of town with a RED, I shot with this camera, I shot with that camera, all those cameras are a little bit different. And basically, what they call a science team, what they do is they can basically provide a lookup table for us. That's basically when a maximize the look of that chip, right? So that we know when the footage comes in, we don't have any information there that we've left on the table. Everything is there that that what they shot, right? And then from there, if we want a certain look, we can make a certain look, but in a simplest form, from having different LUTS per camera, and then having those LUTS translate from HDR, to P3, REC 709, to Dolby Vision theatrical to, you know, all the different types of exhibition mediums, which have different color spaces do have different luminance levels, right? They're in different environments, you know, to be able to have lookup tables at a transition your project from one to the other to the other to the other to the other, quickly, is why color science is completely invaluable. I mean, without them, we would just be like struggling, you know, I mean, it's like, think of it this way, lookup tables are like a mold, right? So you're baking a cookie, you have a very intricate mold of something that has, you know, a whole bunch of lines and a face and eyes and nose and eye, you know, hair and everything else. I mean, if you just put the mold on, you're done. You just were trying to do that by hand. Right, with a piece of dough, I mean, it's gonna take you forever, and it's not going to be as good. So if you look at it that way, and you say, I have all these different exhibition mediums, and I need a mold, if I do a mold for one, and I need that mold look right and another medium, that's what color science does for us.

GB - Where do you go for inspiration when you're trying to build your looks?

SN - I don't really know. I'm really agnostic when it comes to projects. Like right now, I'm working and juggling around like five movies right now. They're all completely different, right? One of them's a musical, another one's drama, another one's a horror, another one's action. So basically, I always take my cues from the cinematographer. The cinematographer has painted that picture that I'm getting and that is ultimately what the queue is, right? You can already get a feel for the what the movies is by the way, the cinematographers lit the scene. So you can get in you could look at a movie even when it's raw and you and you can see the arc of the movie, you can see what it should be like so all the movies that are great, like I almost never listened to any audio. From the cinematographers lighting and now performances, I should be able to decipher what that thing should feel like. And then at that point, I'm just going to color to what I think that thing should feel like. Then I can go back to the dailies and just say, Oh, look, they were, I think I'm on the right track. So I can always kind of pop back to dailies and go, I'm on the right track. But my idea of this is, is a little bit colored different. But let's say I'm doing something cold, and the dailies look warm, I'll say, maybe that's a conversation to be had. I guess you do it long enough you just kind of go by feel. I mean, it really is very, like an instinctual process.

GB - I've worked on projects as an editor and I've had directors come in and be like I base the scene off of this artists work, or this painters work, or this photographers work. Do you do yourself go out to museums and check out exhibits and what have you to keep up on sort of approaches in terms of lighting and what have you?

SN - I have, but you know, again, in general, I mean, when people say they want a certain look for a movie, they're probably referencing another movie. A lot of times, that's completely impossible. Because the way was shot is completely different. We can we can alter and help enhance whatever was shot, but that should never be taken for granted. The cinematographers role as time is going on. I really feel like has been taken for granted. Compared to the, the old days before the DI. It's really not the case that everyone will say that the best looking movies were because you did such a great job as a colorist. There's nothing we can do that's gonna look like the most amazingly shot movie if it's not already amazingly shot. We cannot make something that wasn't shot well look like Academy Award-winning cinematography. It just doesn't work that way. So we can enhance and make things better, but we still can't make something that's not there.

GB - Once you've created a look for a project, how do you make sure that that look is maintained throughout especially, you know, as you start to get, I don't want to say fatigued, but like, you've been on this project for a while. And you don't want to, you know, your eyes get tired, basically.

SN - I mean, that just comes through repetition, right? It's kind of like I've just started running, when you first start running a became to run a mile. But if you run for years, all the time, you can run 20 miles, right. So keeping color on a feature consistent, whether you're doing it with stills, or you just do it instinctually. I mean, that just comes with experience, right? A long, long time ago, when I was before even going into features, there was a mastering colorist, and I remember her telling me, some people cannot hold color throughout the whole feature, they start drifting as time goes on, for whatever reason. And other people can hold color all throughout long projects, an hour, two hour long project, able to do it. And she was always like, I don't know why that is, like, you would think if people had stills to refer back to they could easily do it. Plus, if you had a color correction that you started with it, let's say had 30% desaturation, you can just kind of keep that throughout the whole movie. But, I mean, I have found that through time, that just kind of like the more you do things, the more features that I've gone through that just an easier, it's been. To the point where I can just go through a whole movie, I don't have to refer back to stills that much and, you know, from reel one to reel eight, I don't have to refer back I just, you know, you just kind of learn and you develop a feel. You can even jump through projects or different shows throughout the day. So one could be saturated. One on another project could be desaturated, one could be running cold, another could be running warm. After a while you just build a muscle for your brain and your eyes so that you can just do multiple things st the same time, during the same day. You'll be fine.

GB - How do you take care of your eyes then to make sure?

SN - I'll tell you a good gig a good time to take care of your eyes. It's called listening to books. Right? So this eye doctor that I know, basically said, everyone that he has had as a patient when they were kids through high school, and they had perfect 2020 vision. The moment they went to college, and they studied basically two fields, finance, and law. Where they're constantly reading, he was like, by the time they're in their mid to late 20s, they don't need to glasses, right? If I'm staring at a monitor all day long, that's two or three feet away from me. Every 15-20 minutes, I'm staring at something else. Or I'm looking far, right? So you had to build your, your, your muscles for your eyes to look far and then look close and look for and look close. So the great thing about doing features is I have to stare at a screen that's really far away from me. And then I take a break, let me go check my email, and I'm having my phone in front of my face, which is two feet away from me, then I go back, and my eyes adjust back looking really far. When I'm doing actually TV work, it's harder. I feel like my eyes get much more strain, like my far distance gets more strain. So if I'm not working on a feature, for a while, I'm only doing stuff to a monitor, I really have to like, go home and start looking at things far away. So that's how I take care of my eyes. And if one eye starts getting a little bit blurry, I'll close up the strong guy and just start looking things with the weak eye. Just to get that muscle going. I mean, that's a really great question. Because taking care of your eyes, when you're in this kind of field is very, very critical. Just like any other muscle in your body, you really have to work it. And you really have to take care of it. Right. And so, I have found and I love reading, you know, I find myself reading more now than I ever have, but I don't read for a long time. And I make sure I have a lot of lights, I don't have eye strain. And I never read at night. I just read like with a ton of light on it. And I'll read only for short periods of time and if I really got to get through a book it's Audible man.

GB - So the pulled quote from this will be Stephen says don't read.

SN - Read but listen.

GB - How many trailers do you tend to color correct? When you start it versus like when you first started in your career versus now?

SN - Oh, my God. Well, there was a period in my coloring career where basically I colored trailers full-time for it might have been two to three years with Sony. We had a contract with Sony when I was at the Post Group where we just did all of their trailers. So I color corrected trailers for years. I mean, I've also done thousand trailers. Right. So with all the features that I work on, now I do mostly I do all the trailers for all my features. So yeah, and trailers are great. I mean, it's a completely, it's a little bit of a different way of working. Like, just because your movie looks a certain way, that doesn't mean your trailer is going to look the same way. I mean you're 80% there. Sometimes you'll jigsaw puzzle things around and you got to make that trailer, feel whatever it's got to feel. And sometimes the colors got to change for that, you know, so it's, it's, it's, I mean, I'm really loved trailers. It's really fun.

GB - It's interesting that you have to sort of diverged from the actual movies color. Are you ever worried that people will be like, oh, what the hell? It looks so different.

SN - No, no, no, it's not, you don't deviate that far, but let's just say you have something that's really the desaturated and dark, right? You're going to basically do a trailer and that trailer has got to stand on its own for 30 seconds to 60 seconds. It's not like you got up two hours to get your eyes adjusted to something dark and desaturated, right. Yeah, you can still keep it desaturated, but if it's going on theatrical in a movie theater, you're going to cut that trailer next to another trailer. Let's just say I'm doing one trailer for an action movie, for example, right? So if I'm doing like, "Bourne Ultimatum," for example, yeah and a lot of contrast, I got a lot of cuts. I got a lot of action going on. I'm making that trailer bright and contrasting and colorful, right. And if I'm doing another movie that is going to get, I don't know, cut in, it's going to be in the movie theater. That maybe another trailer next to it, but inherently is dark and desaturated. That thing is going to look twice as dark and desaturated if it's coming after the other trailer. Right? So I know that's got to happen. So then I'll kind of like lift it up a little bit, right? Because you just don't want it to be worse than what it could have been. You know what I mean? Like, if it is already dark and desaturated, as long as the stimulus of bright and contrasting color was right next to it, it looks fine. But if you got stuff bumping around it, that's contrasting and bright and colorful, it's gonna feel twice as dark and saturated. So you know, you kind of make a call on that.

GB - Now, going back to our discussion about books, what books would you recommend for colorists and I want to expand on that because you said you were a big fan of reading, what books would you recommend that you loved?

SN - Well, for coloring, I don't know of any coloring book. You know, the best thing to learn how to color is you basically just get, you know, whether you take a class on it, or you go somewhere where there's a coloring facility, you know, and you can just start, you can just start practicing your color that way. I mean, there's a great book that everybody should read called "Man's Search for Meaning" by Viktor Frank.

GB - Oh, yeah, I read that. Very good. It's heavy, though. I will say.

SN - It's heavy. But it's, it's a fantastic book. Yeah, during this time. Yeah. When this pandemic during this period where, like, nobody can sense when we're going to come out of this. The, there's really no answer. Right? And everyone's been locked down and you know, people, I mean, people, you know, it's a very tough situation right now. But, the book gives you a really good perspective about life, and how to stay positive and how to keep moving forward. So I think, you know, especially when you're in a creative field, too, I mean, you really have to have your emotions in a really good place. Right? Otherwise, it shows up in your work, too.

GB - Yeah.

SN - And I really feel that like, it really shows up in your work. So you just want to be in a really good place, everywhere. So I mean, I would recommend a book.

GB - It's a fantastic book.

SN - Read that book. Yeah.

GB - Now, you've been very generous with your time. So I want to thank you very much for joining me. I do have one last question. I'd like to ask everyone I interview. What would you say your favorite guilty pleasure film is to watch?

SN - Mine?

GB - Yeah.

SN - My guilty pleasure film to watch.? I don't know if it's a guilty pleasure?

GB - That's fine.

SN - Forrest Gump.

GB - Yeah, I usually tell people you know, you're flipping around on Sunday on the television, and it comes up. You're like, I wouldn't have watched this today. But it's on so watch it. Right.

SN - Oh, one of those things.

GB - Yeah.

SN - One of those that that's not like, considered like a great movie is Boiler Room. So that movie. I don't know, for whatever reason. I think I've watched that movie like 20 times, whenever it comes on. I'll watch it.

GB - It's odd that it's not talked about that much. Because I remember watching it and being like, has a really good movie, and then no one really talked about it.

SN - Yeah, right. So, maybe that's it.

GB - Yeah. Well, thank you so much for letting me interview you.

SN - My pleasure.