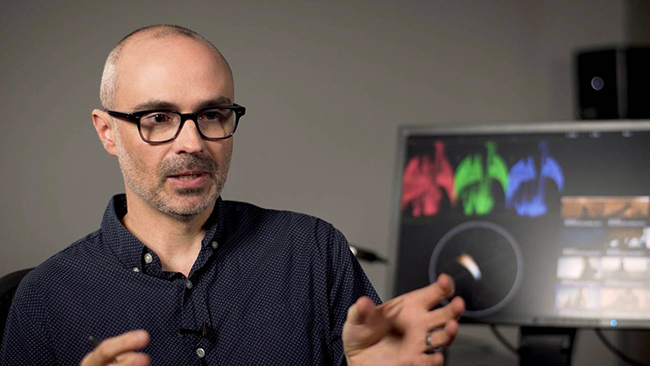

Color Grading and Career Advice with "Mad Max: Fury Road" Colorist Eric Whipp

Colorist Eric Whipp joined Gordon Burkell to answer questions about Mad Max: Fury Road, Color Correction, and give career advice. Eric talks about his workflow while working remotely, as well as the delicate balance of working with clients. If you want to learn more directly from Eric on his processes, his insights and his vast amount of experiences; check out our online class with Eric here.

Eric Whipp was born in Auckland, New Zealand, and raised in Australia. He became a colorist in the 1990s and helped George Miller with his Oscar-winning film, Happy Feet. Today he is a Co-Founder and Senior Colorist at Alter Ego in Toronto, Canada. He reunited with George Miller for the ground-breaking film Mad Max: Fury Road. He most recently finished The Lego Movie 2: The Second Part.

Gordon Burkell (GB) - Hi everyone, I'm Gordon Burkell from Filmmaker U. At FilmmakerU.com we create courses for film professionals to deepen and diversify their existing skill set. Every week on Friday at 2pm Eastern time we go live with a film professional to give you a chance to ask your questions. Now today we're joined by Eric Whipp, and Eric's the colorist for Mad Max Fury Road, The Lego Movie 2: The Second Part, Happy Feet I & II, and he's also one of the Co-owners of Alter Ego post here in Toronto. Hi, Eric. Welcome to filmmaker U live.

Eric Whipp (EW) - Thank you.

GB - I guess I'll start off with a question about which section of Mad Max: Fury Road was the most difficult for you to color?

EW - Good question. It was it was the day for night section when you going into the movie that that was going to be was challenging because the the whole scene was shot during the daytime and it was two to three stops overexposed so it looked nothing like night. So that was a challenge but we had a great method. The idea of it was to overexpose the footage by a couple of stops, which means you have lots of range in your shadows. Then but you don't clip your highlights, make sure that if someone was on set watching scopes and making sure nothing was being clipped. Then in the grade we were able to take that shot, expose it down and got a nice creaminess to it but then we can go in and isolate anything we want in the shadows and lift them up and get all the little bits of detail in there. So you end up with a very, you know, affected kind of look, but it works really well. But to do that It requires a ton of more though. So it took, you know, we knew it going into it. So that was we were like, alright, that aside a few months here, and we'll work on that scene.

GB - When you were working on Mad Max: Fury Road, was there a lot of room to experiment? Or were you sort of tight with your deadlines and had to stay focused?

EW - We got really lucky with the deadline. Actually, we got almost an extra 12 months of post suddenly, because the movie was originally going to be released a year earlier, and you know, pushed by a year. I can't remember but something was going on the World Cup soccer was on and "Star Wars" had moved that date and it was coming out that year. So they said all of a sudden the timeframe shifted. And we were given an extra 12 months, which was amazing. I felt was what was the first part of your question?

GB - Did you get a lot of freedom to experiment?

EW - Yes, we did. In fact, to a degree yes. So the only the only caveat there was a George was very adamant about having a saturated colorful looking film. He always said that. Either we go full black and white or we go full color, but he didn't want to make yet another desaturated post apocalyptic film like every other film has been since probably since the first Mad Max came out, right. So the idea was to come up with something just different and strikingly colorful that you're not used to seeing in a post apocalyptic.

GB - Did any of the experiments that you did actually end up in the film?

EW - We did a lot of work. Especially the nighttime work. Honestly, the nighttime scenes took a lot of work. We had so many different versions. We had great very realistic looking night scenes. We had very steely looking scenes, we had all these but ultimately we have a very rich, you know, we call it like the spaghetti western blue feel. It was like a very blue look, which George really liked. But we had, you know, some of the more realistic versions were great, but you really couldn't see anything because you're struggling to see in the dark, and it's such a high paced action film that we can't be struggling to see anything. So we ended up in a very stylized, lighter kind of rich blue look.

GB - Since working on Mad Max, what have you learned in HDR color grading? Is there any tricks or techniques?

EW - HDR color grading is like a whole new ballgame. The big thing that I've really taken away from it all is, and this is really a little bit of a weird phase in color correction right now, where a lot of especially when you're working on a feature film, the priority is usually let's get the cinema version looking perfect. And that's usually the main priority. But I think we're gonna see that start to change, because I think what really needs to happen as the HDR version should be done first because you really have to get that dynamic range. If you try and do a secondary, it's often a nightmare to try go, "Oh, I didn't see that in the in the sky and oh, now I see that detail. Now we're gonna fix that." And there's a lot of fixing things. Whereas I think what we should start seeing in a lot of films is that we'll work on the HDR master first, which is a little unusual because you're then working essentially on a monitor instead of a cinema screen. And then I think once we get that into a good spot, we then purpose the cinema versions and home versions. So I think really, that's the big takeaway for me is I think you've really got to get that going first.

GB - What can directors do to make your job easier and more fulfilling?

EW - Ah, make my job easier, more fulfilling - stop making changes after we've already finished it.

GB - Or if you can bring you in earlier?

EW - Yes, that is that that is a big thing. Coming in early, getting ideas. Ideally before you shoot because there's things that we can do that can save time or might be easier if you do certain things in camera, sometimes it makes it more difficult later on. But the big thing I think is, is having a bit of time to experiment. And you know, it's the classic thing is time is money and time is the biggest problem when you're rushed and you don't have enough time you don't get a great product. So just the more time and the and the freedom to experiment. I think this is crucial.

GB - When I when I learned film, it was on actual film so you had to shoot as make it look the way it was gonna look as you were shooting pretty much. So are you saying like it's better to shoot it flat?

EW - Not necessarily and it just depends on what you're trying to achieve for certain looks. That might be a perfect thing to do. But I I think the big takeaway is just having a conversation about what your what your ultimate goal is going to be. Because there's some things that look so much better if you just shoot it right in camera, then we don't have to do that much. We can just get a nice look going and then everything will look amazing. However, sometimes when you're going when you're coming up with a very strong post process look. In those cases, you might be better off shooting things in in flat, I don't put grads in the camera to do that, you know, there are things that you might not want to do in the camera that will make it easier to post.

GB - I have a follow up from one of the answers that you did from our course on Filmmaker U that we put together. Can you tell us the brand of 3D LUT Boxes and I guess for those because there are some directors on here and what have you. For those who don't know what a 3D LUT Box is, can you let us know?

EW - So one of the things that we do for a week I do a lot of TV commercial grading and so if you TV commercials we we use these right here we use these LG OLED monitors and in order to get a good calibration on it, you can't just use them straight out of the box so we run behind there there is a 3D LUT Box that will ensure when we probe the monitor and we scope it and calibrate it, that all the colors are pushed in into the exact level so that you're seeing a perfect rec 709 he will do whatever you need to do for TV. So these little LUT boxes you sort of attach to the back and honestly you can use this so many brands out there I think everybody I think Blackmagic makes them in Flanders makes them as a whole, I think we use Flanders. Some are some are noisy than others. That's something you want to research some actually they sound like a train's coming when you plug them in there and if you've got it in the same room as you that could be a problem. Some some have issues they overheat some, you just got to do a bit of research. I think we use the Flanders ones. They're pretty good. I wouldn't say they're perfect. They have to be restarted occasionally this has some issues with them. But it's a it's a great way of getting a large format image because right now when you're looking at all your Pro Series monitors, I think the maximum is like a 30 inch size within two sizes, something you can't get anything bigger and everyone is watching TV commercials and TV at home on 50 or 60 inch TVs. And we want to see the grain structure the same way they see it. We want to see it in a bigger way. So we found that this technique worked really well for monitoring.

GB - Now how much, this is just my own question. How much do you dislike NTSC?

EW - Well, the old TV? Yeah, we don't want to go there anymore. That's a that's you know, it's funny because I grew up in Australia and everything in Australia is 25 frames. And when I came to Canada, I was like, okay, so you're shooting 24 but then it's at 30 frames and you're adding these fields . What are you doing? Didn't make any sense.

GB - How do you go about creating a look or a LUT at the beginning of a project? Also, how do you go about analyzing your source footage for projects?

EW - Okay, so that's a hard question. I don't know how to answer that. I mean, creating a look, it depends on the story, depends on everything, because what we're trying to achieve, but I generally will try a gut instinct, first of what I think will work, and I'll save it, and then I'll scrap it all again. And I'll try it again in a different way. And then I'll scrap that and I'll try it again. And then I'll compare those three and see how any of them look. It's funny when you try and do the same thing three different times, you'll often get a very similar result, but slightly different. And then there's something that you'll usually find something in one of them. It's like, Oh, that was cool. I like that. And what did I do there that was better and so that might then branch off to another look. Then you try something else from there. So I it's just a lot of experimenting I think beginning to really come up with a good a good look like the look development stage can take some time and sometimes you don't focus on something too You will find that you're creating a look and you go, that's great. And then somebody else or a director come in and look at it. Yeah, that's great, but I don't like the green of the grass or something. Yeah. Oh, yeah, I wasn't really looking at that I was just looking at, you know, the skin tone and see sometimes you got to, you know, spend a bit of time and look around the frame and look at every item and every color and find things that might be distracting.

And I can remember the second part of the question.

GB - The second part was how do you analyze your source footage from projects?

EW - I'm not really 100% sure what you mean by analyze the source footage?

GB - I'm thinking when the footage comes in, what do you look for in terms of project?

EW - Yeah, I guess. Again, I think it varies project by project, you know, in a TV commercial will for example I'll scan through. In commercials usually 30 seconds long so it's easy to scan through and you can quickly see if there's any red flags. So I'm often looking for that's going to be a problem or this is going to be one. You're just looking for problem areas or issues or that shot is two stops overexposed. That's why does it look like that? Or why is this one underexposed? How am I going to fix this noise issue? Well, I'll try and just do my kind of my troubleshooting first Yeah. And then I guess in the same feature to you often you look at the entire scene first, and you'll go through and go ok I can see a consistent once we get into close ups, we've got a consistency here that looks good for the wide shot is way too sunny and the close ups are all in shade or vice versa or so you're there will be something that you know you're gonna have to deal with. So it's usually just, I guess, it's like the triage phase of just trying to work out what needs to be addressed and fixed on this scene. Do you have that in the back of your head because the one of the worst mistakes I think colorists make is because they will, I see this all the time is they'll stop on the wide shot. And they will spend hours working on the wide shot and you're grading away a little bit here and they'll put a window here and they're doing so much work. And then they move on to the next shot. And they didn't look at the wide shot was the only one in the sun and none of the other shots are in the sun. And now nothing matches and they can't get it to match and you just spent three hours on a shot that you're probably going to have to turn down and match closer to the other shots and don't sit your look on that. You got to sometimes move around. I'm a big fan of setting a look very quickly. I like to just kind of get out, get a rough look and then move on. And don't spend too much time, but move on and apply that look really quickly to mid shots and close ups and see how that's reacting. You'll quickly find that look might develop more and close up or it might fall apart in a close up and there's no point spending all this time on one shot if it's not going to match with everything else.

GB - Do you recommend learning Baselight alongside Resolve, or if you've already started learning Resolve, just keep with that and keep progressing there?

EW - Honestly, tools they're just here and they're just tools. You can do the same thing on any equipment. So I wouldn't get hung up on the technology, if you're learning Resolve keep going through Resolve, Resolve is a great platform. There's a lot, there's a lot you can do in that. You know, we went Baselight about, you know, 12 years ago, and we just, we liked it. There's just something about the architecture of it. Baselight I like is it's turning into almost more of a compositing tool. So there's a lot you can do in it. So it works for our workflow and what we're trying to do and what I try to do. But it doesn't matter. If we had to switch to Resolve tomorrow, I don't think it'd be a big problem. I'd have to relearn how to do certain things or might not be able to handle certain things that I'm used to doing. But I'd find another way of doing it.

GB - For beginners in for beginning directors or beginning colorists, what would you recommend as sort of a, an essential pipeline to know or an essential thing to know? From the technology?

EW - From the technology? The biggest thing I say this that we have amazing young colorists and assistants that Alter Ego who were learning the trade and coming up through the ranks. And the biggest thing that I always tell them is it's it's, it's kind of like flying, you need your hours in the cockpit. You know, you need your flight time. So the biggest thing is just to get footage and just keep working and keep practicing and you know, whatever it might be, just keep trying and keep your matching and keep your speed up. That's the biggest thing that makes a good colorist is you've seen enough footage that you know how to handle problems and you know how to fix something. And you can do it fast. Because we know when you're sitting in a chair and someone's paying, you know, X amount of dollars per hour you copy that letter. No, I've never seen this before. You've got to know the answer. I mean, sometimes I say that, to be honest, there's times where I've never seen it before. But you really got to have that practice in place. So you know, when I started in industry, we were all on telecine and we were transferring film. You for those who don't know a telecine is we literally put the 35 mil film up on the thing and it live scans that picture and records it to videotape at the same time. And so we would just be you know, we'd line it up and press play and start scrolling through the footage and you'd be grading on the fly and you'd be doing dailies, for example. Dailies were a great training ground because you had to get through, I gotta get through 100,000 people filled today and you haven't, I've only got four hours and you've just got to get through it. In dailies, you would see shots of one shot would be overexposed and it would be three stops under because they messed up and then the DP went, "Oh, I made a mistake and they would fix it." But they might want to use that take so then you got to fix that underexposed shot and then rebalance it back down. And so you had to be really quick and you had to learn on the fly. And I think that's missing a little bit in today's world when you try to be a colorist because you don't have that training ground of, of film, just rolling through your eyes constantly. Everything is shot digitally. Everyone's throwing a LUT Box and seeing it on the monitor, they know it's exposed. It's great, everybody just get some footage but then when something does go wrong, and you do get a shot that's got a big flare in it and everyone says can you cut through the flare or you get a shot that's been underexposed because they ran out of light. How do you fix that? How do you solve those problems? So the best thing is just to get just get that time on the on the system and do it fast. Set time limits for yourself. I use an example of commercials all the time when we're Alter Ego. But if you've got a 30 second commercial, we will tell our assistants like have a go at balancing this out and getting a look on it. Set yourself 15 minutes, don't spend any more time than 15 minutes. You've got to be sit there for half an hour and then shut again, you're going to get stuck in that rut. So just get it done as quickly as possible. And then we'll evaluate and judge that. And then the more you do it, the better you get at it. And it's just time.

GB - In regards to the LG comment that we talked about earlier. Did you find issues with dimming when you make small adjustments on a still frame in the LG monitor?

EW - Yeah, we get jail breakout panels and there is a mood that you can crack in there. And you can turn that dimming off. I have to admit the, the newer models, it's becoming harder and harder to turn that dimming off. But we've we've found ways where you can disable that.

GB - Okay. Do you find yourself using Base Grade inside Baselight? Or do you still use the older tools?

EW - No, I do. I actually love Base Grade. For those who don't know, Baselight, developed a tool a couple of years ago, I think called Base Grade. And it's essentially it's kind of what grading should have always have been. Typically we're used to like shadows, mid tones, highlights, and you've got your, your color within each one of those things. Filmlight came up with something called Base Grade where it's more like an exposure, exposure and color temperature control, and then it works more like a curve. So it's just intuitive like for example, I'm going to I'm going to make fun of your camera right now. I'm looking at your camera. There is a warmness there, right? You're, you're lit under tungsten light, and there's a bit of warmth and stuff. So if I was grading that shot, I'd be like, well, that's too warm. With Base Grade, I can just pull the warmth out in one trackball, and it will literally do a color temperature change and cool you down without having to go where is that one? Is it in the mids or is in the shadow, it's just an overall color temperature change. From then you've got like, almost like a code like adjustment, you can use it on the trackballs, which is very intuitive. So if you want to roll off highlights a little bit more lift shadows, and you can control that in a in a way that is, I guess, more logarithmic and more code like than typical video grade style setup. So the answer that yes, I love Base Grade, but I don't use for everything. It's, it's it's often a quick starting point, and then I move on.

GB - Was Mad Max: Fury Road graded in HDR and when did you do the HDR trim? Did anything change? Apparently people are debating the smoke flares color?

EW - So first of all HDR wasn't a thing when we did Fury Road, it hadn't really taken off and didn't exist. So "Fury Road" was not graded in HDR. However, in saying that when we graded it, we had that idea that it should look like an HDR kind of idea. So we tried to get it as bright and as punchy as we can without losing highlight detail without using shadow detail. And so Warner Brothers did it and they just took it translated as best they could and trimmed it out. Fury Road with such a complex film that it's almost impossible. You couldn't just go back to the film and start again. You'd have to just take the greatest version that we did and adjust that ratio. So I don't really know the answer to that because I didn't do the HDR trim of that. I've done HDR for other things, but not for Fury Road.

GB - I already know the answer to this question, but I'm gonna ask it anyways, because that way people can hear the answer. Wondering if you're going to be working on the follow up to Fury Road that we're hearing rumors about?

EW - A good question. I, I hope so.

GB - That's that's what I assumed the answer would because it's so early right now

EW - I was actually I was slated to I was hoping to go to Australia later this year to work on another film with George. I completely different film. But this whole COVID thing has completely put a damper on a lot of things. So I don't I don't know when that's happening. So we'll see. But I hope so. You know, I've got a reasonably good relationship with George. I love working with him and see where it goes.

GB - And has he already shot that film? Or is he in the process of shooting?

EW - They were ready to shoot in May and it was with Tilda Swinton and Idris Alba. He contracted COVID right as all this was going on in and they we are about to start shooting and so the whole production everything's been shut down.

GB - You mentioned that you use LUT Boxes for LG TVs. Could those LUT Boxes be loaded to via the software video output instead? Would that be a good alternative?

EW - I think that depends on your software. But the the idea behind the LUT Box for the TV - we're getting hung up in the technical things. The idea of the LUT box on the TV is honestly to ensure that your video signal displayed is 100%. Basically your measure your monitor and you're trying to make sure that your monitor is hundred percent meeting true rec 709 signals. So putting that in software, I don't know whether that would be an experiment, but that that could also get dangerous. You know, you got to remember to turn that off when you do any other thing. It could get it could get very complicated, but it's possible I guess maybe?

GB - Here's one that's not technical for you. How do you keep consistency over the skin tone after the look and avoiding it blending with the background, especially the skin back and background fall in the same color range?

EW - Yes. That's the answer to that is Slowly and carefully. There is no easy answer often that is, that's the biggest challenge is you. Most films, it's all about the actor, it's all about the person who is delivering the line or, or in the story at that particular shot. So it's often just drawing the audience's eye. If you can't get a good key, you can use that to your advantage, you can kind of get a good key, you have to run away and if you if you don't, maybe you don't need to maybe it naturally falls off there. Maybe it's the fact that the skin tone sits in the right place, but then there's something else in the frame that is distracting. So you're working on that instead of the skin tone. I don't know there's, it's, that's, you know, it doesn't get any easier. There's no like, magical way like I have this magical technique. I have the same problem as everybody else has, especially when you see an actor against beige wall, and their skin's beige and they're wearing a beige shirt and you're like - oh god. And then someone says to you, can we make that wall blue? There's no there's no easy way. It's just you got to work on it.

GB - What's been the toughest, I guess, or most challenging color requests that you've gotten?

EW - I hate these kinds of questions when I have to think. I find that one of the toughest things is often when people get hung up on wardrobe, or something like that, especially in commercials. We get that a lot in commercials where, you know, you'll come up with a great look. And, and let's say the actor is wearing a very light shade of, let's say, age, just to make it even more hard. Yeah, light beige shirt or something. And then the client will be like can be, we really want that shirt to be like blue or something. That becomes really tricky. Or when there's a major luminance change. If anyone's ever tried grading, that's the thing that I think a lot of directors and DP'S and clients don't necessarily understand compared to what a colorist might understand. Doing major luminance changes in something, it's not that easy. When you swing the color slightly, that's one thing. To take something a little bit blue and make it a little bit green, fine. But when they say can you take my shirt and make it black? That's really hard, because you're going to get little white halo edges unless you get a perfect roto. And then you see someone dancing around for the entire piece and you're just like, I'm gonna have to roto this thing and it's gonna take forever and it's gonna be edges showing and it's gonna be that's the hardest part.

GB - What are your challenges from working when working from home now with COVID stuff?

EW - There's definitely some positives . The commute is amazing. It takes a couple of seconds to get to work. The challenges that we are basically on call constantly . Seemed kind of cool at the beginning where you're like, Oh, I can just do that. Now. I'll just run down and do it. And now it's becoming a bit of a grind where I'm finding myself here at midnight every night working. But, you know, we're pretty lucky we moved a full Base Light system into the basement. I call this my basement light. It works really well like once I've got the footage and the scenes on to the system. It's great. And then, you know, we do live streaming out of here, I've got all that set up. So we can do sessions with clients, you can watch what's happening live and everything, it's amazing. I think the, the big problem is, is you're honestly just getting footage in. Sometimes if certain projects come in and the huge you know, 500 gigs of data that I've got to get into, it takes a long time. And it's a so you find yourself multitasking all the time. I'm either on my laptop downloading footage and or working away at the same time. And that's, that's really the biggest challenge.

GB - How does your process change when you're working on a live action feature versus an animated feature?

EW - It's funny, in one way it's almost exactly the same. I always approach an animated film like it was live action, I imagine that the footage that's come from compositing and lighting is if it came from the camera, and people don't realize this, but it doesn't match. It's not great there is is like inconsistency is because you have different artists doing lighting setups on different shots. So it's like having 50 DP'S trying to light a scene for you, it's not as easy as you think it is. So there's a lot of balancing going on and setups. So I treat that very much like you would in live action, you're just trying to balance something out, get a look going. The difference is is because it's animation, we usually have access to not so if we take the case of Lego, for example, if we have Emmett standing In the scene, I have a perfect cutout of Emmet, I have a matte for him that I can control and I have a matte for his his head and I have a matte for his decals. And I have a matte for his hair and I have a matte for his, his body sleeve color or whatever. I have every individual controls for every element of that which is amazing. But on the flip side of that it's a nightmare because I do have all that control. My stacks get bigger and bigger because we we tend to do a lot of that final finessing. It's almost like a finishing stage of compositing, where compositing might just take us so far. We can handle the rest in color. Yes, we can. But then sometimes that makes it even more complicated in the color suite because you are now doing all these minor minute controls and layering and it gets into some serious compositing like on "Lego" we have this great system where you can control like flares and dirt and grime and things were all embedded, and not necessarily composite into the shot. So we can we can grade it on a clean looking, composite, get a look going, and then we can add some of these layers and blend them through. And so you're doing a lot of work that you would never be doing on a live action films. You wouldn't have all those layers attached. But I don't have to roto.

GB - What are some current series or tell or movies that you're watching right now that are inspiring you or that have impressed you?

EW - Uh, you know what? Right now, the first thing that comes to mind is I'm watching Killing Eve. It's not like your typical it's a it's a network show, but it's not like a network show. It's actually a really good show, really performances is very kooky. I really do like the look the cinematography and the grading. It's not like overly stylized in the grading but the it, but it is, you know, it's got a tonality in a style to it. And it's actually really nice.

GB - Can you talk about how you consider characters and story when you're approaching a project? And if it may be using Fury Road as an example?

EW - The big thing that I've learned over the years is that everything is really ultimately about story. And Fury Road was a great example of that, where it's a fast paced action film, there's a lot going on. And yet, I think maybe I did my job right. And everybody's done that job, right. But you know exactly what each shot is therefore, and you know exactly where to look in each shot and you're not like last in the frame. We used to have this saying, while we're working on Fury Road, and no offense to anyone who worked on this other film was let's not let's make it not like Transformers that was us saying Transformers movies were they're very hectic in their action films as well, but you don't know where to look. It's almost like a mess of metal and you're looking over here and e and is that a good guy? Is that a bad guy? What is going on and you just get confused. When you go into Fury Road, the fast pace of the editing and the style of the film we have to have you laser focused and every shot should have a purpose. So if there's a shot of someone reaching onto a table and picking up a pen, I need to make sure I got it and I better not be looking at the window or anything else. You need to know what that purpose of that shot. So the same thing goes for the characters. What is each shot there for, what is the purpose of it? How do we we bring out their features and performances. On Fury Road, one of the techniques we use is sharpening the eyes, which really helps you connect with the eyes. So that was a little bit laborious, and it's funny I say this now but I can almost guarantee you and Is that there'll be software. I know there will be there will be. There'll be software that does it automatically. But for Fury Road, I had to hand roto every single eyeball in that movie, and it took some time. But it makes a difference. And it's amazing that there'll be a shot where there's someone in the background that says a line, but they're, you know, they're in the background. I didn't roto their eyes, and I play it through and then George would be - is his eye sharp? And your like damnit he caught it! So like, it does make a difference. You can connect with that character instantly when their eyes are pin sharp, and you can see them and it's clear. And so, you know, we did a lot of lot of techniques like that to really just draw you into the character.

GB - Are there any tips for contrast management that you have, and to make for a pleasing contrast range?

EW - So that's an interesting debate because I found through the years of calibrating the difference styles, aesthetic, that contrast changes a lot. Right now, I think and I guess it's sort of my personal preferences. I like the idea of a reasonably contrast image but I don't like to lose too much detail where it matters. So I love it when the when the shadows can roll off into a nice dark area, but I didn't like it when it cliffs and crushes. I like to see that grain structure or a little bit of tiny amount of detail in the very bottom end of the of the dark areas. And the same with the highlights. There are times when a blown out highlight is needed or has to happen, you're looking into the sun or something. But it's just finding that that nice roll off is the challenge. But you know, in saying that 20 years ago, it was all about crushing the blacks. It was all about a whole different style of contrast, that was the coolest thing to do. I think today we're in a more slightly refined version of it. So managing contrast, I find different tools work for different things. In Base Light, there's different types of grading tools and sometimes contrast works better in one tool than it will in another. A big thing is also the terminology or what makes a contrast image is not actually contrast. It's often your mids are just too high or something and you lower your mids down and suddenly the picture looks more contrasty. If you haven't actually dial the contrast knob and or anything, you're just changing the values of the of the frame. I don't know if that answers your question other than you just see it's constantly evolving and you're looking through shots all the time trying to keep that level that crunch to the image that is pleasing for whatever project you're working on.

GB - How do you manage a client who's asking for something that's impossible? Or just a bad idea? And how do you guide them to a good idea or good direction?

EW - That's a great question. This is something that I deal with all the time, especially in commercials. Sometimes you will often have ideas that don't match footage, people have an idea or elaborate reference. If I had $1, for every time someone gave me the Tree of Life reference, it would be very rich. So I get the, you know, I got these two guys in a bank against a white wall. We want it to look like the Tree of Life. You're like it doesn't look anything like the "Tree of Life." I think the challenge is, don't be afraid to talk. That's the big thing that I think a lot of colorists or a lot of people learning forget. It's a conversation you need to have this conversation with your directors are your DP's and or your clients. You talk them through it. I've been guilty of it too getting when someone says to me - can we, whatever, we make this brighter, and I'm like, it's not gonna look good, right. But I will do it. And sometimes I do surprise myself you're like, Okay, you know what, if I do it this way, it does work. And the other thing too bear in mind is sometimes they will have a lot of people will have requests where they, they might say it wrong. But what they're looking for is actually something different than what they're saying. So, you know, I'll get it all the time where someone will say, the shop needs more saturation, can you make it more saturated? And often, what I'll do is actually just look at the mid tones, and they go, oh, that's great. So I didn't touch saturation at all. You're just trying to get more density and richness out of the image without actually making it more saturated. As a colorist, you might look at the frame and go, this can't handle any more saturation. It's like, looking at my scope. It's like no, this is not going to work. But if you do something else, or a tiny bit more contrast and something then all of a sudden it just has more apparent saturation and things will come to life. I guess the the trick is, don't be afraid to have that conversation. Don't be afraid to say, well, let's try it. If it doesn't work, don't do it. I shouldn't really say this because this is really giving away secrets. I've definitely been in situations before where the request has come through that I think is completely the wrong thing to do. So I will sometimes actually do the look and go a little I'll do it almost to an extreme version of what they're asking for. Because I know it's all gonna fall apart and and then like, oh, that doesn't work. No, it doesn't. So if you do it subtly, and it's borderline and they might buy it, but if you really don't want them to go there then sometimes that's that's a technique. Generally you're working with good people and you're trying to come up with an idea and talk them through it. The worst thing you can do as a colorist, you're always in the colorist chair working and you don't know what it's like to be in a color session with a colorist because you other colorist, right? I had to experience a couple of times where I've had to come in and sit in the back of the room on somebody else's session. I found it was really frustrating sometimes when I didn't know what was going on, because they weren't talking. And someone will say, oh, let's make that a little bit more blue and I'm watching the screen going, okay, I know it's gonna go more blue in a second. And then I watched the image and it goes so slowly, I can barely perceive that it's gone blue and all of a sudden the shop moves off and rolling. We're playing it. Did we make it look what's happening? So it becomes really frustrating sitting in the passenger seat when you don't know what's going on. So if the colorist is saying, All right, here's a little bit more blue. What do you think here? It was here it is now? Yeah, I think that's better and you have that conversation. But if you try and do it quietly and subtly behind everyone's back, it's impossible.

GB - Do you have anywhere that you go to for inspiration for new looks or styles?

EW - No nowhere specific. I'm always looking at films and TV shows and great stills photography. I love looking at some of that sort of stuff like just seeing if it's like your typical magazine kind of shoots or something that is a really stylized look. You wonder what that would look like if we tried that in motion. I guess like everything we get inspired by life and by nature. You know, sometimes it's as simple as you go outside and the light shining through the trees and you're like, I'm gonna try and do that on the next job. Something can be something as simple as that.

GB - Is there a type of photography that you like to do or do you like just take your camera with you everywhere.

EW - I like a bit of everything. Like a bit of a I'm famous for taking really boring holiday photos of skies. Because I have a sky library for sky replacement so often it's just literally a sky.

GB - If you're brought on in early enough do you make LUTS for shows or movies, or do you find that you inherit them from the DIT's?

EW - I haven't actually really had a version where I've inherited a LUT. It's always been a combination of one we've already had or something that, you know, something that kind of exists thats been tweaked. I've definitely had LUTS from DP's that a good bit often I find that there's something about it that I know is going to cause me problems. I'll get this LUT and it has a nice film look and everything but there's like a second color in there that you coming through in the light. Okay, so what do I do when I get to the let's say green is not really existed in that LUT. What do I do when I get to the forest scene and I can't get green? So I'll often go like I know what you're trying to achieve with that LUT, but I might have one already that works or or find one and tweak it.

GB - How do you create a look for the entire film, but then still make sure that each scene has its own unique look in the film, given that each scenes are shot differently?

EW - Fury Road is a great example of that, because I think overall it has a unified look. But then, if we had graded the entire movie exactly the same way, it would be a very boring movie to watch because it's essentially all in the same location for two hours. So we had to break it up, we had to find new ways of doing things. Once we have this idea where it's very gritty, saturated - when I say saturated, it's rich and saturated. It's not actually an overly saturated movie. When I first started on Fury Road, I think the dailies colorist had done some work and then George is sitting in the edit and he's like, I just want more saturation out of it and so someone had like wound the saturation knob on the dailies just to get it looking more saturated. And he's like okay, that's better I can this is more like what I'm looking for. But I came in and I looked at that and I was like, oh my God, this looks like a bad 1980's music video where you know the skins all red, the skies were totally blue and everything. Sure its saturated, but you can't just you can't just wind that saturation on. Once you come up with a look that you develop, whether it be a tinge of coolness in the shadows on everything no matter what or a lot of contrast in the mid tones, or something that is a unified kind of procedure - then you can come up with looks per scene that makes sense of that story. So we would have looks after the dust storm, should have dust on everywhere and have that really bleached look, and everything's really white. That was part of that look for that fight scene that happened after the dust storm. But then vice versa, in this film we did something like 600 sky replacements. Towards the end of the film, when they roll out and they motorbikes on the salt flat and they're trying to decide whether they should go back to the Citadel or keep going. That was a pivotal moment the film where we wanted the audience to feel is this a good decision? Or is this a bad decision? We need to be with them on that. Like, I don't know which way to go like going back to where we came sounds like a ludicrous idea. but maybe it's the best idea. So what we ended up doing with that, even though it was shot like any other scene in the movie we put a stormy cloudy kind of sky behind it. So you have that sense of like when you're standing out in the sun, but the storms coming, but is it going to pass or is it going to be okay? And it's not? So suddenly we're introducing the weather as another character, as if the weather is telling the story whether this is going to work out well or not. And so, you just come up with different looks per scene, but everything has its unified look.

GB - How does your process change when a DP or Director asks you to create a LUT? What are the perimeters that that you look to tweak in your LUTs?

EW - I refer to LUT's more like your overall conversion. If you're shooting LUT C and we're gonna go to this and this LUTwill convert it all and give you a nice nice tonality and that is like the overall LUT. It's not like we create the looks in the LUT. The LUT is just very basic. It's not doing that much. So I think the question there is more about not so much the LUT, but more about the looks we are seeing which is like a combination of grades and tweaks and, and other things that then I can carry over from shot to shot to shot. I don't have to have that on the entire film. If you have something really strong in LUT, you're really getting handcuffed to a look. You'd never be able to do anything else. It's better to be able to have something that does a nice conversion for you and roll it off in the way but then control the rest of the image through grading intervals.

GB - When you come in to the final color, how important are on-set grading choices via the CDL or are they revisited, tweaked or removed, overall per shot?

EW - It happens more on TV shows for sure. For the features that I've done, honestly, that doesn't happen at all. We don't use any of that data. It's really whatever happened on set happened on set. It's a whole new ball game and a whole different look. It's a whole completely different thing. We'll offer it to how things looked in the dailies, we'll look at it and go, okay, there's something I liked about this shot. Let's replicate that. So yeah, I haven't on all the films that I've done, we haven't had that kind of process. Or, or it's been the other way, like in in, especially in the animated films where we get an early that we're actually developing, you know, sometimes what happens in those animated films is like, the lighting department will give you a really quick rough render of the scene. We'll bring it into color and we'll grade that. We'll shape it and work it. Then this we think is looking really good. So then that becomes a reference, it goes back to lighting, and then lighting then kind of lights to that look. So by the time it comes back to me again, I start again because I don't want to double it up and then sort of come up with a new look.

GB - What can set designers do to help make your life easier?

EW - That's a great question. One thing that I learned very early on when I first started grading was how important production design and set design is. I remember I was doing some great TV shows and grading some of these beautifully production designed shows. Soon after I was doing like somebody's student short film and it was it was awful. I remember the young DP was like "why does my stuff not look like a Spielberg film? I'm lighting it right and I'm doing it right." It's because you have anything to shoot, you're shooting at a white drywall. There is nothing here. There's no set. There's no production design. Then they kind of clicked to him. So that's been that is a huge thing. I think one thing that I would say that is is often useful is to be wary of skin tone color if you want your actors to really pop against the background. Maybe don't shoot them all in skin tone beige colored walls. That's going to be a big problem or in saying that though, Mad Max was basically the entire thing is beige. If you know do you want to have you know, if it's a sci-fi film or something that maybe put everything in a cool tone in the background and then the skin will stand out against it all and vice versa.

GB - Do you think that you'll be increasing these remote sessions and moving forward do you think you'll have a preference for working with clients in the room or separate from a distance?

EW - I always would rather prefer to do it in a room with people for sure. But I think possibly, realistically, I think it's going to be like this for a while. I've been doing live streaming sessions for 10 years or so now and we started doing it a long time ago to Alter Ego. There is a ,there is knack to it. Often the feed will have a couple seconds of delay. Then you're in a situation where you go which one do you like better this one or this one, but then it's switching seconds later. You never want to be in that situation. So you learn little tricks of how to do it.

GB - My fear would be more is their monitor calibrated?

EW - That is a big thing. Everything we're doing is kind of standard rec 709 commercial colorspace. So most of our clients are on MAC's and we sort of know that an average MAC has a certain screen that is pretty close. So we've got a good guide of what they're looking at, and we've sort of tweaked our methods to that. It can be a big problem where you do get feedback sometimes where people say they see it looks a bit green, and I'm looking at my monitors again and it's not green. So at that point, I'll say look, I what I see is not green and I think you have to trust me here.

GB - Is there a particular colorist or multiple colorists from past or present day whose work you admire?

EW - Yes, Jill Bogdanowicz who did Grand Budapest Hotel. I love the style of those films. The look, I think she's amazing. I think she does great work. Whenever she's got something coming out, I always want to watch it.

GB - Is there any career advice you have for a young colorist just starting out. What would say they do to get into the assistant route and get into a company like yours at Alter Ego?

EW - Get out there and do it. Practice, practice, practice, practice. You know, what we're normally looking for when we're hiring assistants, we're looking for people that are really passionate about this. If you're actually really passionate about color, then stick with it and stay that course. Do your things you're in work, understand the principles of light, do some photography. You know, if you've taken crappy photos of your own and worked out how to how to fix them, that's a good place to start because you'll know how to deal with some of these problems. Get some face to face time like none of us are afraid to say hi and meet you and reach out to connect.

GB - My next question is about doing an HDR session virtually. IPads don't have great luminance in HDR, have you tried doing an HDR session virtually?

EW - No, we haven't done any HDR work at all. Virtually. Everything we're doing right now, like we're in this sort of lockdown phase is 100% commercials or music videos, none of its HDR. If we were doing HDR, then it we really would need to make sure that we are streaming to some HDR monitor of some sort. I'm not sure how other people are doing it. Luckily, the majority of our work right now is all to the standard rec 709. So we're pretty lucky that way. Yeah, I didn't really know how to answer that. I'm sure a lot more people in LA doing a lot of TV shows and they are probably struggling with that. I would say probably the best way of getting around that is the colorist would see in HDR, but everybody else would be the SDI version streaming.

GB - To clarify an earlier question, how is it that you manage to create a LUT for a reference for a show? How do you manage to keep things in limit, but still have a look that people onset can refer to.

EW - We have the overall LUT that isn't really, I don't think he's actually doing that much. It's just sort of doing more of a tonality change and, but then we'll often have looks. So then at that point was a couple of different ways we can do that. One is we can create a look, it's almost like once I get a look on a scene, I can take that overall look but turn off all of my other layers. I don't want windows and things on there, I just kind of turn all that stuff off and just leave the base look in there. Then we export that and say that is going to be the look for that scene. You can then get more specific and go shot by shot. So this is the look for this job. This is this one's underexposed. So you use this LUT, you can go into that much detail. Or the other way you can do is depending on what system you're using and who's doing the compositing is - we can actually go into a lot more detail where the entire grade will actually carry over and run on Nuke. So the compositor can be compositing and they can literally turn the entire grading stack on in Nuke and can see it all graded with track windows everything. There's multiple different ways and you have to work out on each project how feasible it is.

GB - When you're working in commercials, a lot of clients ask for very neutral grades that don't go far beyond just bouncing, contrast and saturation. How do you make a current commercial grade more interesting, and how do you convince clients to go in a more interesting direction?

EW - Thats a good question. Sometimes you are definitely stuck to a guideline, this is the brand colors and you're there's not much you can do about it. But there is there's usually room wiggle room and everything and I'm always looking for how can I make it better and how can I make it a bit more interesting? I always do a grade before the clients come in the room. I always have it. I always have the entire commercial kind of graded before they walk in because if they've already got a preconceived idea, which they often do. Bear in mind, everyone's been editing a commercial for a couple of weeks and they've been staring at the dailies for a couple of weeks. So they start to get used to that and they might be a shot or a couple of shots in the dailies where everything looks a little bit overexposed, but they're kind of they used to that now. That's what they think is normal. So when they come in and you expose it properly, they go," well, it's really dark." No, it's actually exposed properly, what you were looking at was overexposed. So often it's good to have something prepared so that you can show it to them. There's other little tricks in grading, which is a subtle thing, which is sometimes you don't want to show a look that I is amazing. But I won't show that straight up. You hold it back, because people will come in and they'll go, "Oh, this looks great. But what if it had a little bit more... Oh, like this" and then you have the one prepared that you've already you know, you want to go there.

GB - What's the best strategy for getting deep focus cinematography since everything is sharp like in the 1940s, but with the color like you did in Mad Max.

EW - The focus thing is obviously going to be more in the lensing. But I think it comes down to the problem. I mean, you know what, I'm dealing with this right now, because I've been doing a lot of ads that have been shot on iPhone because it's all they can send the same cameras and crews out so they send people iPhones film yourself. That inherently has a problem because when you shoot on an iPhone, it is infinite focus, there's no depth of field and we get into the grading room and all of a sudden this I don't know where to look. Everything is competing for my attention. Because there's no different field. So that's where we use a lot of toning. We just really want to guide your eye like and let's make sure that their face is a little bit crisper and a little bit brighter than all the other things or something like that just find a technique to draw your eye.

Want to hear more from Eric? The art of apprenticeship has changed since the evolution of digital color grading. In the past, knowledge was passed down from master to apprentice when a colorist shared their room with their assistants. Now you can have that experience, learn proven techniques, strategies, organization, and problem-solving straight from the color room with Eric Whipp. Get unparalleled insight on some of the greatest films of all time, first hand from the colorist who graded them. Sign up for his Filmmaker U class here.

Every week, Filmmaker U is joined by award-winning filmmakers and creatives from the film and television industry. Please join us weekly to ask your questions live with our guest or watch or vast catalog of talented lineup of past interviewees on our YouTube page or facebook page.