Ron Moore & The Creation of "For All ManKind"

In this interview, Filmmaker U is joined by For All Mankind creator and showrunner Ronald Moore and his go-to editor Michael O'Halloran. Ronald and Michael's team efforts include Battlestar Galactica, Outlander, Star Trek, and of course, the new Apple+ TV series For All Man Kind.

The discussion focuses on authenticity in historical specific fiction, show running and developing a relationship that lasts multiple series and more!

Gordon Burkell (GB) Hi, Ron and Michael, welcome to FilmmakerU.com.

Ron Moore (RM) Glad to be here.

Ron Moore (RM) Glad to be here.

Michael O'Halloran (MO) Happy to be here.

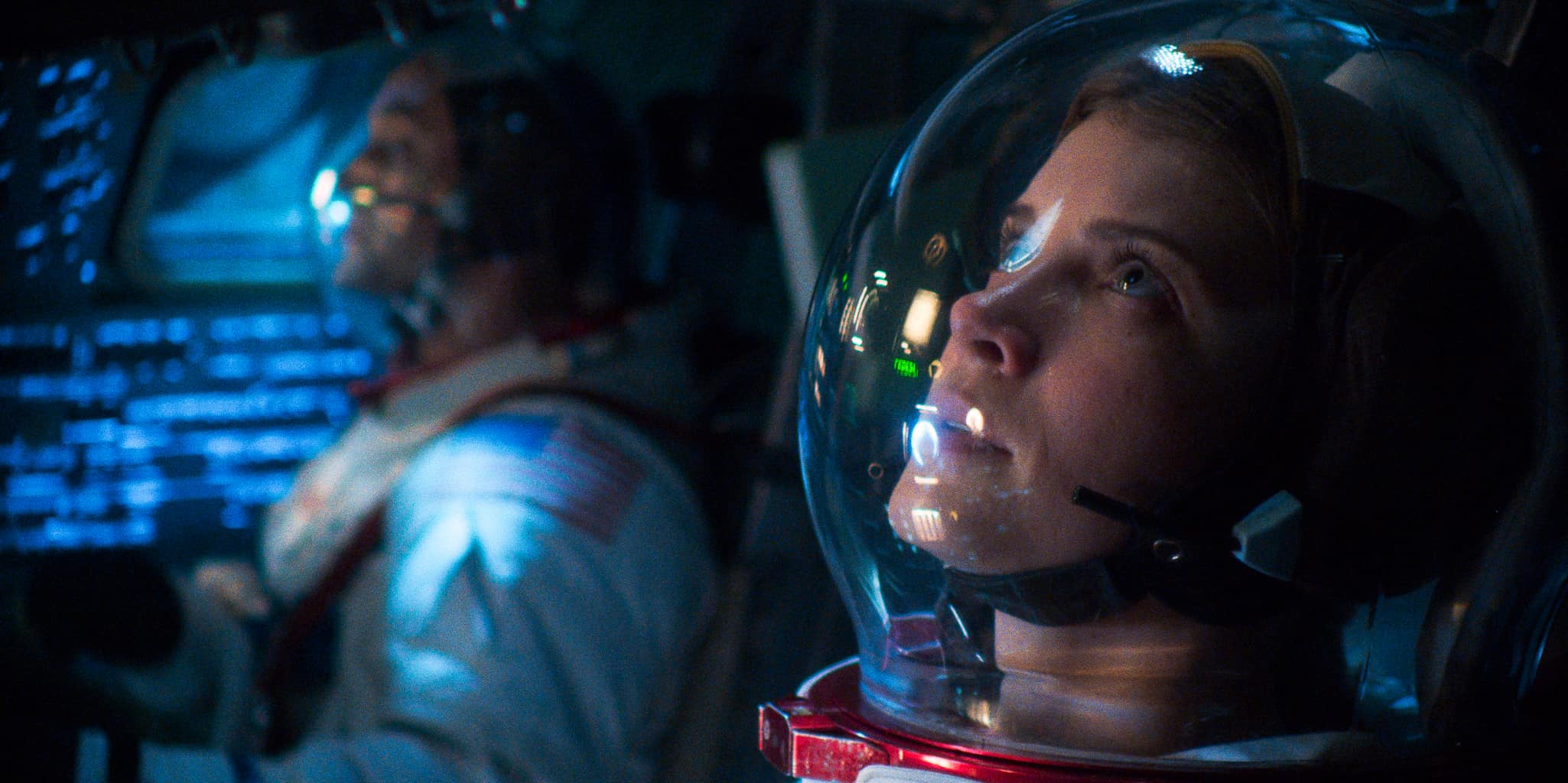

GB One of the questions I was asking Mike, before you got on Ron, was how much did you guys do in CG? And how much did you actually have real, there on the set, like was the lander real?

RM It really depended on what the scene was I mean the LEM, the lunar module, we built practically the lower part, the descent stage with the ladder and the legs and the engine underneath and then we had a sizable footprint of moonscape on the soundstage, as well, the moonscape was ever-changing. Dan Bishop, our Production Designer pretty much kept going in and moving rocks and changing elevations and all that was practical.

But the top of the lander and all the landscape and sometimes the visors themselves were digital and you know, it really depended on the scene as a fair amount of complicated work back and forth, especially when astronauts were moving about on the surface, they were on wires, they're stunt people. Then we would comp that into various landscapes. There was always some kind of practical element with it. That's probably the only pure CG scenes in the show are the exteriors, exteriors of spaceships and so on. Even then, like at the end, in the latter episodes of season one that was a whole sequence where we had astronauts doing an EBA on the spacecraft that had an accident. And that was, again, a combination of live actors on the soundstage being held up with wires and a piece of the spacecraft as an exterior that we built. And then that was all brought into the CG world.

GB As soon as I announced that we were going to be interviewing you guys, one of the first things that happened was I got a direct message from someone who worked on the show. And they said, first you guys are great to work with. But second, and more importantly, they said that, Ron, you are very focused on details that most people will miss...

RM My intention is also known as an obsession. Unhealthy attention. I grew up as a fan and aficionado of the space program. So even as you know, I'm old enough to have seen Neil Armstrong walk on the moon as a little kid. And then through the 70s, I was obsessed with NASA and I wrote letters to them and they sent me things back and photos and I read lots of books and pamphlets and stuff. So I really kind of geek out on all the specific equipment and what NASA really did and what they were really capable of and how the equipment functioned and how they worked.

Through the years I'd always sort of been annoyed when I would see other depictions of the space program, I was like, "that's not how it really works, that's not accurate!"

So I sent out the word to all the departments to obsess about the details like I did and of course then in post-production that comes back to bite us in the ass because you're watching cuts, and Mikey and I are going through the tech notes, and it's like, "oh, yeah, there's a lot [issues], the valve is turned the wrong way on somebody's spacesuit and, this is not right, for that dial..." and so you end up spending all this money in post-production to fix these little digital details.

At a certain point, I just go, okay, this one's on me. I asked for this kind of trouble. But even I'm saying okay, we're not going to correct that. And so it's something we just learned to live with. But I do like being as close to authentic as we can manage.

GB So how awesome was it to see the lunar lander in your space? You essentially had a replica.

RM It was amazing, you know, to go down there and stand next to the lander and when you stand next to it, you're really struck by how large the vehicle really is. And it's a tower. We didn't have the top of it and just the descent stage as a towering piece of equipment. By contrast, when you go inside the spacecraft because we had complete, you know, actual replicas of the command module and the lunar module, when you would get inside them, they were so small and very claustrophobic and the walls, the real ones, the walls, the metal was very thin. Somebody famously said that you could poke a screwdriver through the skin of the LEM. It was like that to save weight as best they could. So everything was reduced to bare minimum metal tolerances for everything.

GB So how awesome was it to see the lunar lander in your space? You essentially had a replica.

RM It was amazing, you know, to go down there and stand next to the lander and when you stand next to it, you're really struck by how large the vehicle really is. And it's a tower. We didn't have the top of it and just the descent stage as a towering piece of equipment. By contrast, when you go inside the spacecraft because we had complete, you know, actual replicas of the command module and the lunar module, when you would get inside them, they were so small and very claustrophobic and the walls, the real ones, the walls, the metal was very thin. Somebody famously said that you could poke a screwdriver through the skin of the LEM. It was like that to save weight as best they could. So everything was reduced to bare minimum metal tolerances for everything.

And when you would get inside the command module, it was tiny. I mean, it's like it is like being in a, in a sedan, you know, just like a car crammed with equipment, very few windows, and then we put a spacesuit on and then for our purposes, put a camera in there, and it's super cramped. Some of the actors had moments of claustrophobia being shot inside the LEM, but it was a thrill. It was really a kick to be able to go down and walk around that stuff that I'd grown up with and always dreamed about and fantasized about actually getting to do it.

GB As a team, how did you guys work together? Because Ron, you're one of the creators, but you're also one of the writers for this. And in editing, Mike, it's always been referred to as the final rewrite. So what how would you guys describe your relationship as a team to bring this to the screen?

MH That's pretty accurate. Ron always calls the editing process his final draft. He says the one he writes on paper, the first. The one they direct is the second, and the final draft is what we do in the edit room.

GB As a team, how did you guys work together? Because Ron, you're one of the creators, but you're also one of the writers for this. And in editing, Mike, it's always been referred to as the final rewrite. So what how would you guys describe your relationship as a team to bring this to the screen?

MH That's pretty accurate. Ron always calls the editing process his final draft. He says the one he writes on paper, the first. The one they direct is the second, and the final draft is what we do in the edit room.

All showrunners have a different process in my experience. Ron likes to come in. We watch the show together. We don't stop, which is nice. A lot of people stop as we go. So Ron gets to take in the full thing and then we go back and we start doing notes. Again, I don't really do them in front of you Ron the first time. They're broader nodes, you know, structural notes, lifts, something like how can we make the performance from this particular actor a little more comical, less angry or something like that.

Then I'll take a few days, sometimes a little longer, depending on how many notes [I get] and Ron will come back, we'll show it to him again then we get into the weeds a bit more. Then we start looking at certain performances and a lot more of the visual effects stuff. Fixing a lot of things like Ron described, the technical stuff. One we're concentrating a lot on now is there's a patch on one of the uniforms. That, I couldn't tell the difference at first, but it is slightly off Ron, right? And we're now digitally fixing it.

RM Yeah there are a set of wings because some of the astronauts were naval aviators. They have a specific set of wings that they wear on their flight suits. And we had the wrong one on the day and then didn't catch it for a long time. So we had to go back in and digitally repair it and put in the different wings on the costume.

RM Yeah there are a set of wings because some of the astronauts were naval aviators. They have a specific set of wings that they wear on their flight suits. And we had the wrong one on the day and then didn't catch it for a long time. So we had to go back in and digitally repair it and put in the different wings on the costume.

GB When you guys get together and start working, how much change do you put into each episode. Yesterday I interviewed some doc editors and docs change daily. But you guys are a little more structured by the script. So were there a lot of changes in the post process and how did you come to your final decisions?

RM It really varies by the episode. Some episodes are just strong from the first cut and all you're really doing is looking to lift time or polish performances. Lifting time is a big thing in television, we're always trying to get this show back to its fighting wait at least on a streaming service. Something like "Outlander," for Starz, there's a specific runtime you're trying to hit.

In fact, before I, we play the episode, I always say "So where are we in terms of time," because that's the first thought I have to deal with, trying to get it to the correct runtime. And then there are some episodes that are just problematic for whatever reason. A lot of times the script was unstructured or there were problems in shooting or, you know, a variety of reasons. You're watching an episode and I'm going, Oh, my God, this doesn't work. It doesn't hang together. It's not paced correctly. The rhythm isn't working. Sometimes the story itself is really a problem and wow, what do we do with it now?

In those circumstances, then it's a wash the first cut, and we'll just talk about it frankly, at the end like "wow, okay, we're gonna have to rework this whole thing and you start pulling out various editorial tricks. Okay. Can we change this to make it linear? Or the episode we're making is a nonlinear episode, let's put the end at the beginning and do flashback structures let's start mixing up storylines let's take the A story make it the B story" and Mike just starts playing around with ideas until you finally find some version that starts to gather steam. And you're like, I think we're finally onto something on this episode and then you just have to kind of really sit on it and bear down and then keep going.

There have been episodes where we've gone all the way back to dailies or had Mikey go and find items. Like he's gone all the way back to dailies and kind of reassembled the show. It's part of the process. Fortunately, that's not usually the usual thing. Usually, the episodes are in pretty good shape and you're just trying to figure out kinks and storylines here and there.

MH They are the most challenging, but they're also the most satisfying in the end, aren't they Ron? As far as....

RM Yeah.

MO ...on a personal level, you're just like, wow, we just cracked that one.

RM Yeah, like in "Outlander," when we did "The Wedding Show" first season. The wedding episode was a big thing because it was obviously "A" a wedding and any television show where you're marrying the principles, that's a landmark event. And "B" it was a big part of the book, and the fans are gonna be excited about it. It was a big promo piece. And so we watched the first cut, and it was like, "Whoa, this isn't playing," you know, just wasn't quite put together. The director's done a great job of directing a lot of good stuff, but the cut itself just didn't live. Some of it was structural in the script. And there is always a variety of reasons. And then Mikey, you were in the U.S. and I was in Scotland...

MO I flew over to Scotland to work with you on that one. And we spent a good two weeks and just completely ripped it apart and started from scratch. And I think in the end, that's one of the fan favorites now, right?

RM Yeah. And we pulled out all the stops on that one. We were doing tricks like running footage backwards to get the right head turn, flopping images and stealing stuff from in-between takes and everything. But in the end, it was very satisfying because it was a really good episode and we felt a tremendous sense of accomplishment that the material was there, the story was there, it was all there and you just had to carve the stone and let the statue come out.

GB Wow. Now, one of the things I noticed in the story in For all Mankind is that it's more about following the program instead of, you know, here's the main character and we just follow them episode to episode. What were some of the hills you had to climb to get that to work? Or what were some of the struggles you had to overcome to make that flow from episode to episode?

RM It was interesting. It was something we talked about in the writers room early on, because of the nature of the show was to start moving through time rather aggressively, even in season one, we start in 1969. And by the end of season one, we're in 1974. So you're moving through years, and the series overall, at the end of season one, we jump to 1983 for season two, and so every year, every season, we're gonna keep jumping more or less. So you start looking at it in a different way. Because if you start falling, if you get too focused on specific characters, well, their stories are going to drop off and they're going to die. They're going to age out and other generations are going to come forward.

MH They are the most challenging, but they're also the most satisfying in the end, aren't they Ron? As far as....

RM Yeah.

MO ...on a personal level, you're just like, wow, we just cracked that one.

RM Yeah, like in "Outlander," when we did "The Wedding Show" first season. The wedding episode was a big thing because it was obviously "A" a wedding and any television show where you're marrying the principles, that's a landmark event. And "B" it was a big part of the book, and the fans are gonna be excited about it. It was a big promo piece. And so we watched the first cut, and it was like, "Whoa, this isn't playing," you know, just wasn't quite put together. The director's done a great job of directing a lot of good stuff, but the cut itself just didn't live. Some of it was structural in the script. And there is always a variety of reasons. And then Mikey, you were in the U.S. and I was in Scotland...

MO I flew over to Scotland to work with you on that one. And we spent a good two weeks and just completely ripped it apart and started from scratch. And I think in the end, that's one of the fan favorites now, right?

RM Yeah. And we pulled out all the stops on that one. We were doing tricks like running footage backwards to get the right head turn, flopping images and stealing stuff from in-between takes and everything. But in the end, it was very satisfying because it was a really good episode and we felt a tremendous sense of accomplishment that the material was there, the story was there, it was all there and you just had to carve the stone and let the statue come out.

GB Wow. Now, one of the things I noticed in the story in For all Mankind is that it's more about following the program instead of, you know, here's the main character and we just follow them episode to episode. What were some of the hills you had to climb to get that to work? Or what were some of the struggles you had to overcome to make that flow from episode to episode?

RM It was interesting. It was something we talked about in the writers room early on, because of the nature of the show was to start moving through time rather aggressively, even in season one, we start in 1969. And by the end of season one, we're in 1974. So you're moving through years, and the series overall, at the end of season one, we jump to 1983 for season two, and so every year, every season, we're gonna keep jumping more or less. So you start looking at it in a different way. Because if you start falling, if you get too focused on specific characters, well, their stories are going to drop off and they're going to die. They're going to age out and other generations are going to come forward.

So right away the very nature of the show means it is more about the program. Yes, it's a character piece and you're talking about the characters that live within it, but the macro story is really the story of NASA in an alternate universe and how that would all work. It was a unique structure. And it took a while for us in the writer's room to figure that out. What is the rhythm of it? How long do you stay with a particular story on a particular point in time, and when you jump ahead by even a couple of years, you pretty much clip off the stories that you've been telling in terms of plot, character, and story is still going and then you're picking up the character a little later on in his or her life.

Structurally I started harkening back to a series called "Centennial," a miniseries in the 80s I believe that was based on a... I think a James Michener novel that I watched as a kid and it was, I loved it. I was fascinated with it, it was one of those big epic pieces. I don't know how many 12 hour miniseries back in the day when they did miniseries like that, but it told the story of a town called Centennial, Colorado and it literally starts with the formation of the earth, and then the Native Americans come, and then there's stories with them. Then French trappers and the first settlers, and it basically goes all the way through the generations up until the 1980s.

There was something really interesting about watching television like that where you would get invested in certain characters, and then watch them young, grow old, have children, then they would die, then their children would carry on the story and then their grandchildren. And there was an overlapping of character arcs all the way through it. So that kind of influenced me. And we talked about a lot of the writers room because that was essentially the style of showing the work we're telling here. Where we're moving through generationally, not through the centuries like "Centennial" did, but even through decades, it's still a similar kind of storytelling.

GB Because this is an alternate universe, as you mentioned, We still have real people in the show. I'm wondering, where do you, as a creator, draw the line in terms of making up fiction for a real person as a character?

RM It's a fine line. It was one of the first things we tackled, how many real-life historical figures would we have in the show and how to portray them, and then you get involved in legal affairs and all that kinds of legal issues associated with it too. But on a creative level, we just kind of took the point of view early on that, essentially, we were going to be fair to these people.

John Glenn really did feel that way and it's documented and he said it on camera and that was just something he said. And something he really felt. With a character like Deke Slayton, who's in the show, as a main character in the show over many episodes, clearly didn't do any of the things he did in our series, but we tried to make a true to the spirit of who Dean was, and we try to have him embrace, for a man of his time, what his attitudes would be, sort of the father figure of the astronaut corps.

Same with Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin and anybody who was real. We tried to make them close to who we understood them to be historically, Verner von Braun as a more complicated choice because his backstory of Nazi Germany and building the V2 and his relationship with the concentration camp and the labor camp nearby is a complicated one that most people weren't familiar with because it wasn't talked about over the span of his lifetime for the most part after the end of the war. But it was true and it did come out. There was a book called "Operation Paperclip," which we relied on and there were other documents, things like his army interrogations. And what we tried to say was, here's what the historical facts are in that hearing room and then here's what we know Verner said himself about his experience that he didn't know. And he always kind of slid around exactly what he did know what he didn't see. And he always maintained he didn't really know and that he was promoted in the SS, and it wasn't really his choice.

Then we kind of left to the viewers to decide how they wanted to feel about that and to play it like that. So we tried to be as fair as we could to Verner while acknowledging the historical truth of what was there.

GB What would you guys say was the toughest scene for you guys to work on?

MO Well, there's two. There are those that are technically challenging and then there are the ones that are just not working dramatically sometimes. And they're very different in that way. A lot of the green screen stuff can be. Well, I'll tell you which one it is Ron. In season one, an episode you wrote "Hi Bob." Where the helmets weren't connected.

RM Oh my god.

MO Something happened on set while they were shooting and early in the day the helmets weren't connecting to the suit. So we had to digitally go in and [fix them] and that's a lot of screentime. I mean, 10-15 minutes worth, right? Every shot.

RM Yeah, it was a huge scene and it was a pivotal scene in the show. There were a variety of reasons if something happened on the day on the set, I'm sure it's all about time and trying to try to make your day but also the choice was made at the time not to shoot it with the visor, which is something we [had to] go back and forth with the visual effects supervisor. On the day, we'll usually say on this shot in this angle, we want the glass visor and in this one, we don't. We'll put it in Later. In this particular set scene, they shot the whole thing without the visor. And there's this bar or this piece of costume, or spacesuit that goes around that connects to the top of the helmet that then got folded in because the visor wasn't there to hold it out. So when you tried to put a digital visor in front of it, this bottom piece didn't match up anymore.

So then you had to recreate the bottom piece and then you had to worry about the light spill under this, it was this whole thing. So as a result, technically, it was so expensive to literally do it in every single shot that Mikey and I had to go in and recut it to try to de-emphasize as much as we could the problems and it did force us to make some creative choices like we've gone inside the helmets a few times we just pushed in under the footage got inside the helmet to avoid having to do this whole repair work and then kind of put a little bit of color over like gold or something to kind of give it a certain look and feel, so you feel like you were inside the helmet for the first time and it was actually kind of effective. It worked pretty well in the cut and the whole scene had to be recut so that, you know the trick, visual effects is usually the longer the take is the cheaper it is. Whereas if you have multiple takes of visual effects that's much more expensive than almost exponentially.

Mikey and I then had to figure out what shots we could hold for a longer period, which takes we can hold for a longer time, how long we could sit in the two-shot and how long you could hold the close up and it just suddenly the technical budgetary aspects was driving the creative which is always a pain in the ass but we did manage to still make it good.

MO And it kills you because you don't want to be spending money on big expensive CG space moonshots and to have to sacrifice some of the budget for that is very frustrating.

GB That's one of the technical ones was there a particular story element that was... and I don't mean like the story wasn't working, but getting it to sort of click a bit better getting to punch it up a bit.

MO In the pilot, the first episode Ron, you know, we go back and forth a bunch with making the astronauts a little more fun and likeable? They were kind of too down and depressed about losing the moon. So we recut a bunch of scenes to emphasize that they weren't as depressed or down about [losing the moon] that was a challenge. I think we even had to pick up a few shots to make it work.

RM We did some reshoots. We picked up a few things. Yeah, trying to get it just the way I wrote it. I wrote it that they were hit by the Russians, beating them to the moon and they took it very hard, but they took it so hard in the initial cut that it was just a really depressing time. So we had to find lighter moments we had to find and pick up some footage and even some sequences.

MO The bar where they throw the bottles at....

RM Yeah.

MO ...the dartboard. That was the section we reshot with a...

RM We reshot that completely.

MO Yeah, the singing wasn't part of the initial script. The first version was just them kind of sitting around the bar depressed and whining about it a little bit.

RM A lot of times you're just struggling with the scene creatively because it's not hitting the right note. And then inevitably, you... You want the characters on a very important moment to sell or realize they weren't looking in the right direction or that there's no coverage that was just in a wider shot. And there's a lot of creative things that are struggles just somewhat technically because you don't have the technical pieces to tell the story that way or sometimes I'm changing my mind about what that scene is about. The intention was it's about this and I think it's more effective if we emphasize this other character, make it her story and his story. Emphasize that. But how do we make that work because the footage wasn't designed to fit together that way. So it's a puzzle, taking things apart and trying to put them back together in different structures that we spend our time on.

MO Also sometimes you'll notice something that you didn't expect in a good way from the performance or whatever, and you'll change it, because you want to emphasize something that the director or the actor brought to the scene that you weren't expecting to redo scenes for that reason sometimes.

RM Yeah, that's great. Sometimes you're like, "Wow, look at that, what we just did over there. Let's try to make it all about that. That's where the short story is."

MO It happens quite a bit actually,

GB In terms of tone, you hinted that you might want to shift the sort of perspective and tone in a scene. Tone requires so many departments, and of course, editing, being one of them, to make sure that the tone of the scene works. I'm wondering, Ron from the scriptwriting phase to the editing with Mike, how do you guys work to sort of mold the tone and get it right?

RM It's kind of intuitive, you're just watching the cut and I'm at the end of it. I'm usually just talking about my feelings and feeling it's too slow or it's too fast and the emotions are not registering or it's too bombastic and we haven't earned it or the humor isn't working, we should cut those jokes because the jokes are just laying there and it's just usually a very intuitive subjective point of view as I'm watching it.

As Mikey and I really dig into it and he starts playing with it. Music is incredibly important in the process. I was just saying it's very important because it changes everything and it's Mikey trying out different pieces of scores or songs. It changes everything about the scene and changes the mood of the whole episode. I always talk about episodes, generally, as being music they have bass and melodies and tempos and high points and crescendos. All it's very musical kind of composition in my head at least. So as I'm watching, I'm always talking about the rhythm of the show, we need to slow down the show right here, we need to pick up the pace right here, we need to build to a climax. And one of the most important things of all, when you're just looking at it, overall, is to figure out where the show's over. But sometimes we write too much like we've missed the dramatic ending of a particular story. It's like that's the end of the story and everything else we have to cut and people are sometimes shocked especially the original writer might be horrified that I'm cutting the rest of that scene or the cutting scenes that went after it.

Truth is the show is over right then and you have to kind of know that intuitively and say that's the end of the show. So then you can almost backfill it. Well the climax of the show is here and then there's high points and low points and places where you need some quiet before it explodes again. It's all about rhythm and pace in a lot of ways.

GB How about yourself Mike?

MO Ron has really great instinct about the tone and we've been working together for so many years now that I'm gonna have very similar sensibilities. But even when I'm you know, assembling a scene from first initial assembly, I'll have sometimes the music playing as I'm doing it. So if I know it's like a scene with a lot of tension, or you know, a lot of action I'll pick a piece of music. We have our composers music, so I often use that because you know, it'll be similar and a cut it to that beat or pace, which is really helpful way to do it that I find.

GB Now we've got a question from our viewers here. They said your VFX story with the helmet was a great example of solving a problem. But Aaron is interested in knowing - "I'm curious if any lessons over the years from "Star Trek" to now where a decision was made, just to solve a problem versus a story one, is there any ones that had to be solved for just tech reasons that you look back on?"

RM Oh, yeah, there's lots of errors, there's things that end up in shots that you need to fix and people say the wrong thing. We have to go fix it in ADR, all kinds of garden variety errors that just occur on any production, and then sometimes there are things that are just genuinely wrong, things I didn't catch in the script and I'm watching it in editorial and going, oh my god, did he just say that totally is wrong. It's so wrong. That just contradicts what we're doing, oh my god. Now I've got to reconstruct the scene and we've got to reshoot this or I wasn't there.

GB How about yourself Mike?

MO Ron has really great instinct about the tone and we've been working together for so many years now that I'm gonna have very similar sensibilities. But even when I'm you know, assembling a scene from first initial assembly, I'll have sometimes the music playing as I'm doing it. So if I know it's like a scene with a lot of tension, or you know, a lot of action I'll pick a piece of music. We have our composers music, so I often use that because you know, it'll be similar and a cut it to that beat or pace, which is really helpful way to do it that I find.

GB Now we've got a question from our viewers here. They said your VFX story with the helmet was a great example of solving a problem. But Aaron is interested in knowing - "I'm curious if any lessons over the years from "Star Trek" to now where a decision was made, just to solve a problem versus a story one, is there any ones that had to be solved for just tech reasons that you look back on?"

RM Oh, yeah, there's lots of errors, there's things that end up in shots that you need to fix and people say the wrong thing. We have to go fix it in ADR, all kinds of garden variety errors that just occur on any production, and then sometimes there are things that are just genuinely wrong, things I didn't catch in the script and I'm watching it in editorial and going, oh my god, did he just say that totally is wrong. It's so wrong. That just contradicts what we're doing, oh my god. Now I've got to reconstruct the scene and we've got to reshoot this or I wasn't there.

There was an episode in "Battlestar Galactica" which I, I did a whole podcast about that episode that started off by me saying "okay, today we're gonna talk about an episode that didn't work very well. And when I first saw the first cut of it, I hated it. I was like, so mortified. I walked outside and smoked a cigarette. It was just like, what the hell am I gonna do about this?" Then I went in and did the trick I talked about earlier, I took the ending and put it at the beginning and made the whole show a flashback as a bandaid to at least give it some tension, but it was what it was. There was not much I could really do to salvage the show because the truth was the problems were in the script. And I didn't see them in the script and I wasn't there during production to see so I'd kind of walked away from a lot of aspects of that particular episode. Then it bit me in the ass, and was like okay, now we've got to figure out what to do with this.

We're just stuck but technical things are always happening everything from doors that don't close or wrong person looking out the window. So a lot of times screen direction is wrong. The characters are looking in the wrong places. Mikey's a wizard at fixing eyelines. I don't know how much... 30% of his time must be spent fixing eyelines and making the actors actually look at what they're supposed to be looking at. And we're constantly cheating and using split screens to marry performances together. There's all kinds of things.

MO A really good one the other day; I was fixing one that, I guess it somehow slipped through the cracks in the script and one of the characters kept being referred to as captains instead of as Admiral. So I had to go vice versa. I had to go back and, you know, play all that on the characters back so they could fit in the word Captain in instead.

GB Someone else is wanting to know, you guys talked about screening the cuts, and they want to know if you guys have any tricks for staying objective after or I guess staying fresh because Ron, you've been going with us since the script phase and Mike you've been spending hours with the footage so how do you stay fresh and objective while watching the footage?

MO I think it gets a little more difficult for me because I'm watching it. I'll watch it 100 - 200 times sometimes and one day I'll watch it like "oh my god, this is great. It's working perfectly." And the next day I'm looking at it I'm like, "oh, but none of this works." So it's great to have Ron come in and say "no, no calm down. That's all great. That's not a problem. This is a problem, but that is not a problem." So that we both have someone who hasn't watched it hundreds of times and has only seen it 30 times come in.

RM For me there's a point in the life of the show where I kind of don't watch dailies anymore. I have Creative Producers and other Producers that are watching. They're literally they're on the set, and then they watch dailies and sometimes I'll catch up and late at night, I'll just start scanning the dailies obsessively, and watching tons of minutes, and it's three o'clock in the morning before I know it.

MO A really good one the other day; I was fixing one that, I guess it somehow slipped through the cracks in the script and one of the characters kept being referred to as captains instead of as Admiral. So I had to go vice versa. I had to go back and, you know, play all that on the characters back so they could fit in the word Captain in instead.

GB Someone else is wanting to know, you guys talked about screening the cuts, and they want to know if you guys have any tricks for staying objective after or I guess staying fresh because Ron, you've been going with us since the script phase and Mike you've been spending hours with the footage so how do you stay fresh and objective while watching the footage?

MO I think it gets a little more difficult for me because I'm watching it. I'll watch it 100 - 200 times sometimes and one day I'll watch it like "oh my god, this is great. It's working perfectly." And the next day I'm looking at it I'm like, "oh, but none of this works." So it's great to have Ron come in and say "no, no calm down. That's all great. That's not a problem. This is a problem, but that is not a problem." So that we both have someone who hasn't watched it hundreds of times and has only seen it 30 times come in.

RM For me there's a point in the life of the show where I kind of don't watch dailies anymore. I have Creative Producers and other Producers that are watching. They're literally they're on the set, and then they watch dailies and sometimes I'll catch up and late at night, I'll just start scanning the dailies obsessively, and watching tons of minutes, and it's three o'clock in the morning before I know it.

By and large, I haven't seen the show in a while. By the time I sit in the editing bay, script is weeks ago, the production shoot is quite a while ago still, and I haven't seen most of the dailies. So it's kind of a fresh experience when I sit down a lot of times it's like, oh, yeah, what's in this? I don't even remember what's in this episode. It's kind of like a very pure experience and I can be objective, or actually, you shouldn't be objective. You need to be subjective. I have to sort of go by how it affects me. What's my take on it? Do I feel good about it? Am I unhappy with it? Did it make me laugh? Did it make me cry? What do I want to feel here and then go with that.

Now in the sense of problematic episodes like "The Wedding Show," we're looking at the footage over and over again, there does become a point where you're not quite sure anymore. Because you watch this so many times that the fear is, its bad, and I don't see it because I've gotten used to this cut. I've gotten used to the way that this is playing and I like it, but am I just used to it? Or do I genuinely like it. Until at a certain point, I have to open it up to other people who then give you their notes and you ignore most of them and go with your instinct anyway.

MO Sometimes there are even scenes that you know, were real problematic. And then we finally get them to work just on a level where it tracks and make sense. And we're so satisfied, but then we realize oh... but is it any good dramatically?

RM You know, does it work dramatically? That's the killer. Sometimes we've worked on scenes for a very long time. And then we cut them in the end.

MO Sometimes there are even scenes that you know, were real problematic. And then we finally get them to work just on a level where it tracks and make sense. And we're so satisfied, but then we realize oh... but is it any good dramatically?

RM You know, does it work dramatically? That's the killer. Sometimes we've worked on scenes for a very long time. And then we cut them in the end.

GB We have another question that's come in and they want to know in the show how much does the story change from script to edit?

MO It depends on the episode some of them like Ron said earlier, are pretty smooth and yeah, the cut is almost exactly scripted. And then others, like "The Wedding" episode or you know, a handful other ones, you wouldn't recognize them from the original script. If you read it, while you're watching, you're like, huh?

RM Yeah, it'd be hard to even track it through the script because we've jumbled up the storytelling and really changed the way things are playing.

GB Now I have one last question. I like to ask everyone I interview and that's what would you say is your guilty pleasure film or show to watch?

MO I'm currently watching which I'm loving is "The Great" on Hulu. A satarical Catherine the Great drama.

RM "Roadhouse."

GB Well, thank you guys so much for letting me talk with you and letting people ask their questions.